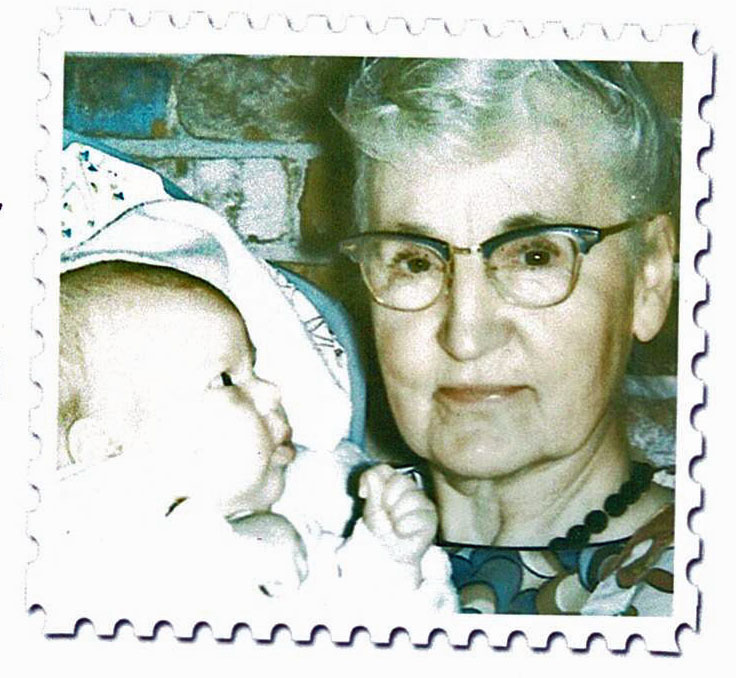

Week 49 -Written- Helen Wolfe Lonski (my mother)

Well-chosen words, piles of poems, long letters to the editor of the local newspaper and stories scribbled on scraps of paper abounded. Helen Margaret Wolfe Lonski left these items in my care. That was a lot of written words to go through. She knew written words caused conflict.

She wrote these two short poems about the responsibility people had to use words wisely.

Responsibility One

Every time your tongue’s unkind

Something dies

In another soul.

If to healing words

Voice is given

Something shriveled

Comes alive

In another being.

Responsibility Two

Words wound,

Words mend,

Words hurt,

Words heal.

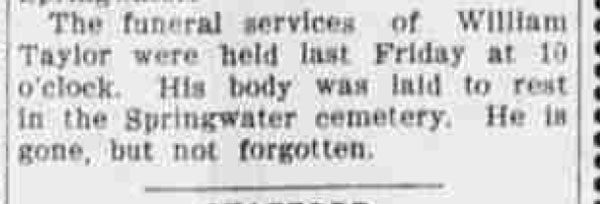

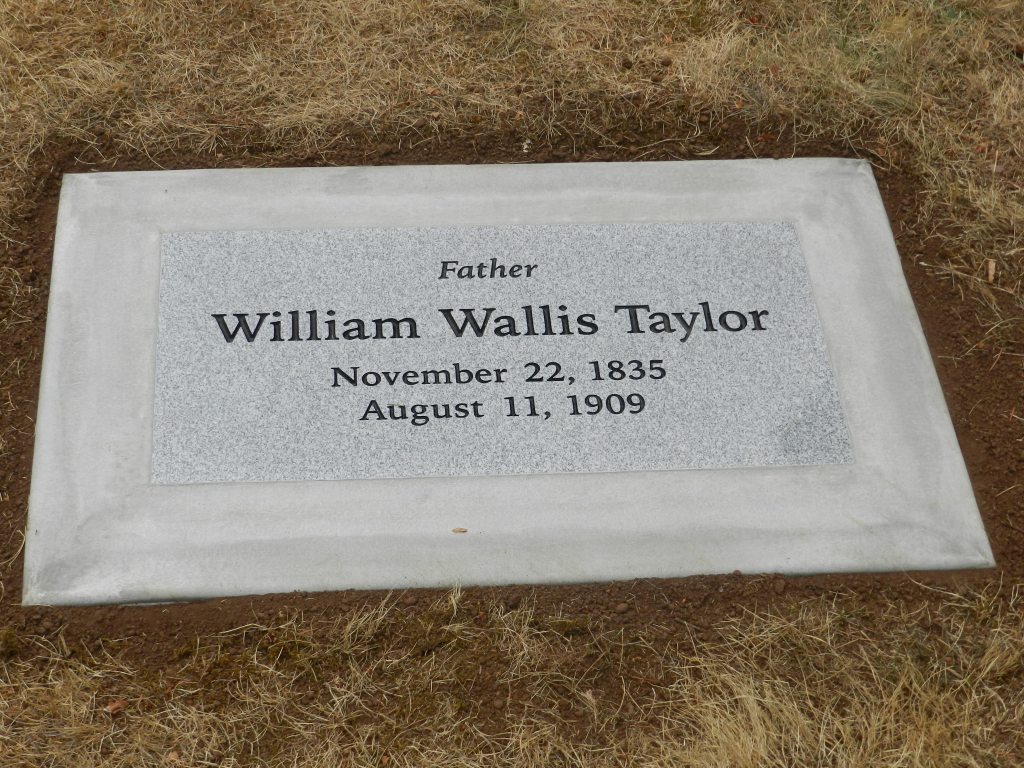

Even as a young child stories, books and words fascinated her. Growing up on a hop farm in Brownsville, Oregon. She did chores. She wrote about one chore she really liked.

One of the fun jobs we had was keeping the cows out of the corn patch that grew in their grazing ground. Mother gave us a blanket and books. She packed us a good lunch in a basket. I got two shining dimes a day for my labor. The older children got more. How rich I felt with two small silver pieces. One thousand dollars could not have been as much. When I saved $2.00 in dimes I took my family to the ice cream parlor for a treat. That store is still in Brownsville with its old crooked planked floor.

Then Helen’s family consisted of her father, Bert Wolfe and her mother Edna Olsen Wolfe. Her two older siblings were Harry and Mildred.

Helen had been born on December 26, 1917. Then the Wolfes lived on Bert’s hop farm near Independence, Oregon. They moved to Brownsville in 1920 where Bert established a new hop farm. Helen didn’t remember the Independence farm.

One of Helen’ early memories was the sad one. The family buried Helen’s father, Bert Wolfe in the Brownsville Pioneer Cemetery in November of 1925. Helen wrote a poem about this. She called it,

To A Father Asleep

They told me Time would heal the wound

That passing years would leave the mark

Only Of a vague pain of thy gentle memory.

They lied. I felt then only numbness and a strange awe

That grownups usually indifferent, were suddenly kind.

Taking us three children by the hand

My aunt led us

For one last look at your dear face.

It seemed you were quietly sleeping.

If I could but touch your hand

I longed to tell you

Of the letter that had come for you that day,

The sadness of the dog, Laddie, since you went away,

But the urgent pressure on my shoulder restrained me.

My aunt spoke slowly

"Your father was a man greatly beloved."

She motioned toward a bank of flowers

Making the air heavy with their perfume,

White Lilies, gorgeous hot house flowers.

I missed the honest gleam of buttercups,

The homely glow of dandelions.

Flowers that you had graciously accepted

From small sticky fingers.

Helen favorite grown up woman was the aunt in this poem who spoke slowly and held her hand. Helen wanted to be like this aunt, her mother’s only sister, Sigrid Olsen. Sigrid received her nursing diploma from the College of Medical Evangelists at White Memorial School of Nursing in 1920. Helen Wolfe received hers from the same nursing program in October of 1941. While Helen studied at Loma Linda campus in California, she happily wrote this poem.

Laughter

Laughter is an elusive thing,

As hard to hold as quicksilver,

Bright, flashing through your fingers.

Glinting from many friendly voices

As sunbeams on granite cliffs,

And sparkling out from happy days

As moon light on moving waters.

At White Memorial Hospital

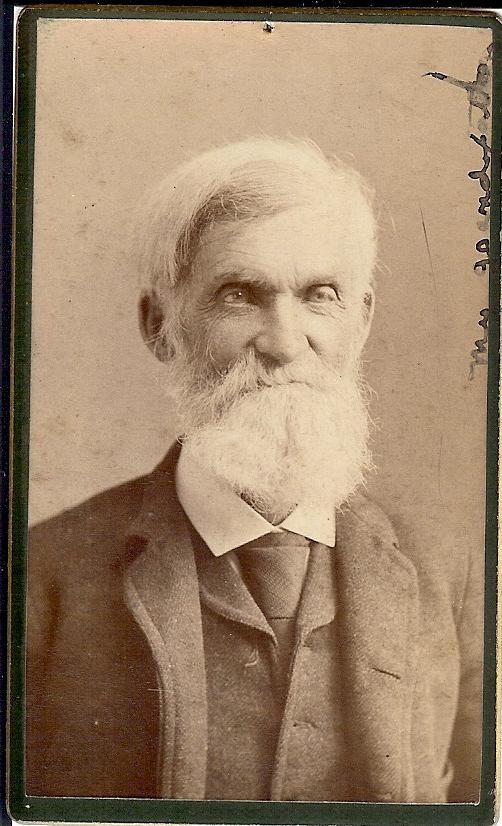

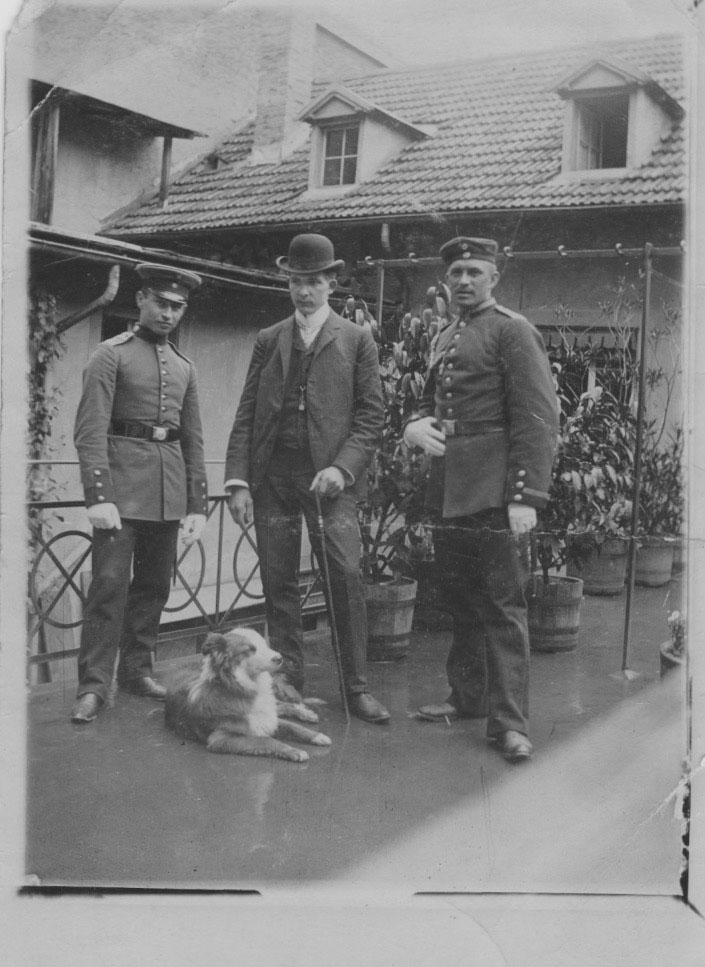

Here is a photo of her dressed in white to view a surgery.

After a year of book studies at Loma Linda, Helen went to Los Angeles. She was a student nurse at White Memorial Hospital. While there, she did rotations. She didn’t like all the rounds as she implies in the next poem.

L.A. County General, Hospital Before Antibiotics

It seemed to me

As up and down we walked

These contaminated halls,

That little bugs crawled in and out,

And over all the walls.

The floor it moved beneath our feet

Almost of its own accord.

Dread diplococcus and sporocysts

Swat lustily aboard.

The kids all yelled with a hearty will

And resisted nose drops mightily.

Vexed and perplexed, I endeavored to quell

The noise that eddied around me.

As I soothed their unhappy little noses

Bathed their bodies, and changed their beds

Life was full of big red roses,

Howling kids, and 'coughs, and sneezes.

Sorry, I regretted choosing nursing,

When I landed on contagious diseases.

Helen graduated from White Memorial School of Nursing on October 1, 1941. She received a certificate from the California Board of Nurses Examiners stating she was a registered nurse.

Brawley

At the end of her nurse’s training, she went to work at a 6-bed hospital in Brawley. This private hospital served the Brawley Community in the 1930s and 1940s. In 1950, the larger Pioneers Memorial Hospital opened in Brawley.

Helen received a letter from the California State Nurse’s Association. The postmark reads Brawley, California, 30 Sep 1942. The 610 Imperial Ave. address matches that of the Brawley Hospital.

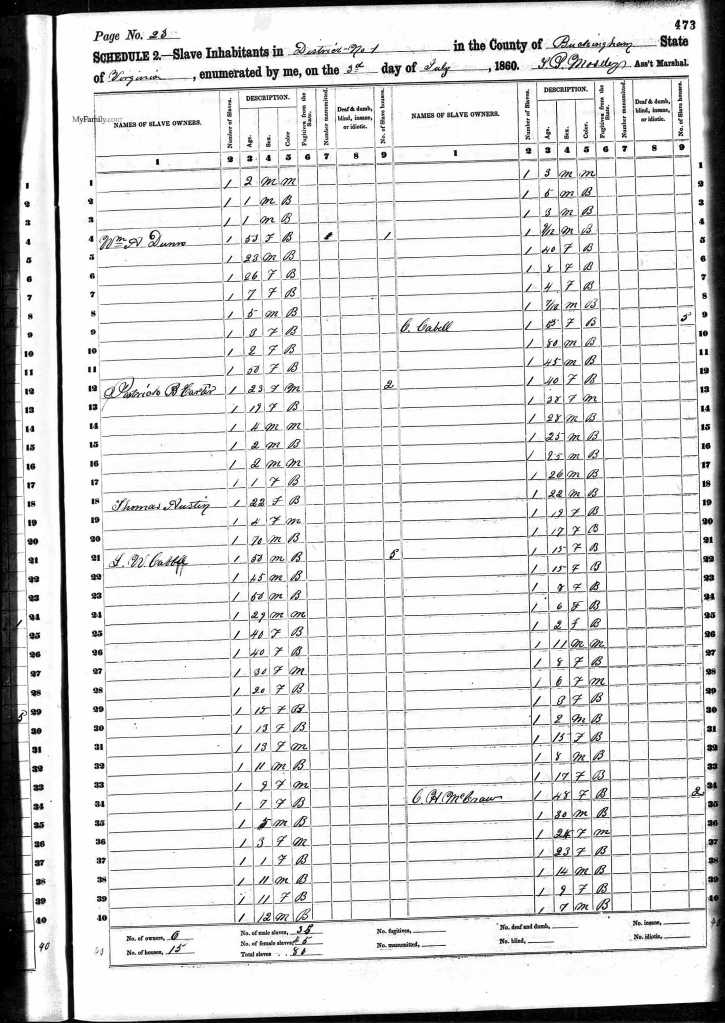

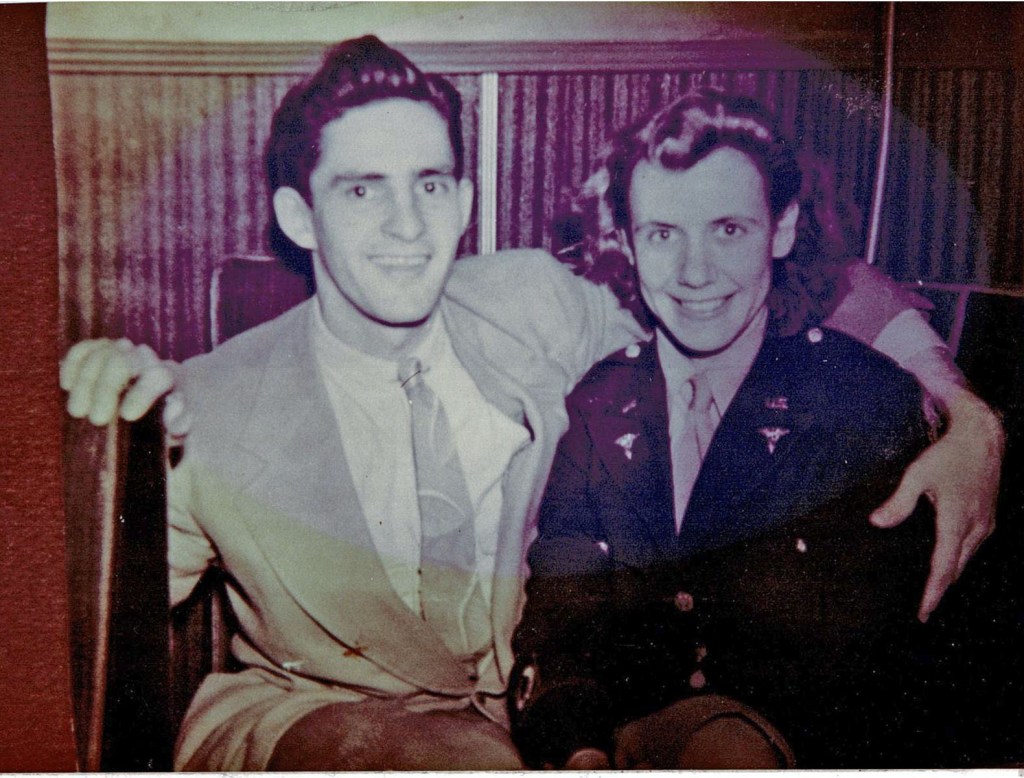

It was here that she met Albert. Before they dated each other they dated mutual friends. Albert Lonski did his basic training at Camp Elliott, near San Diego. He, a marine sergeant, shipped out in November of 1942. Camp Elliott trained Marine recruits for the South Pacific.

The Colorado Desert, Brawley’s location, had a tropical climate. Albert wrote to Helen. She answered in kind, and they exchanged letters throughout the war.

Helen wrote this poem.

Desert Night East of L.A.,California

We see

Night light soft and dim,

On the white of the yuccas,

Ten million bright stars,

A round full moon

Tangled in the tall pines.

We hear

The tiny tinkle of a small brook.

The hillside holds its breath

We dare not speak

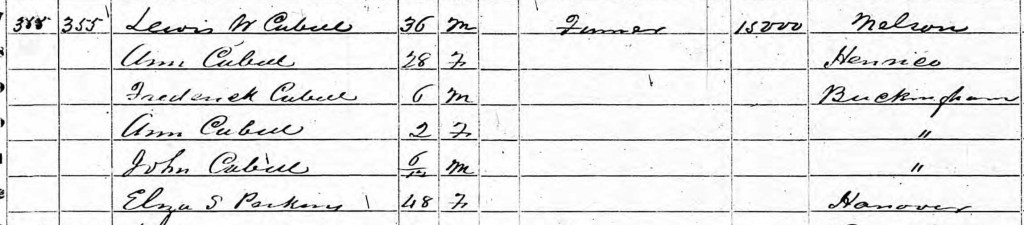

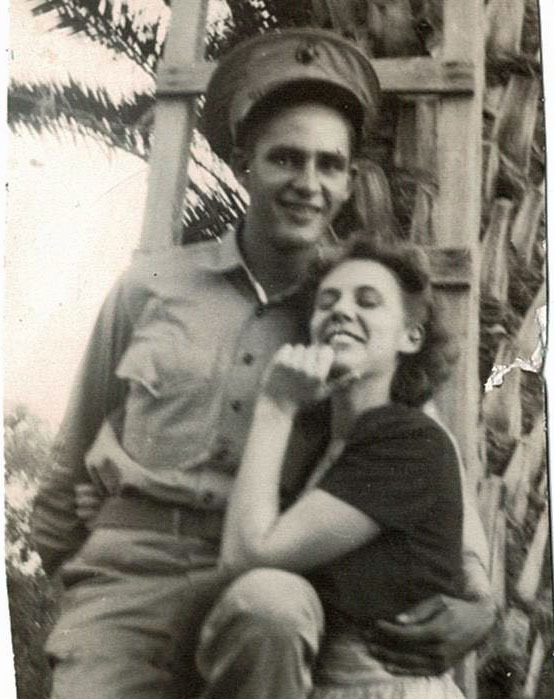

left, Albert and Helen in Brawley—-right, Albert’s wallet photo of Helen

From Albert Stationed in the South Pacific

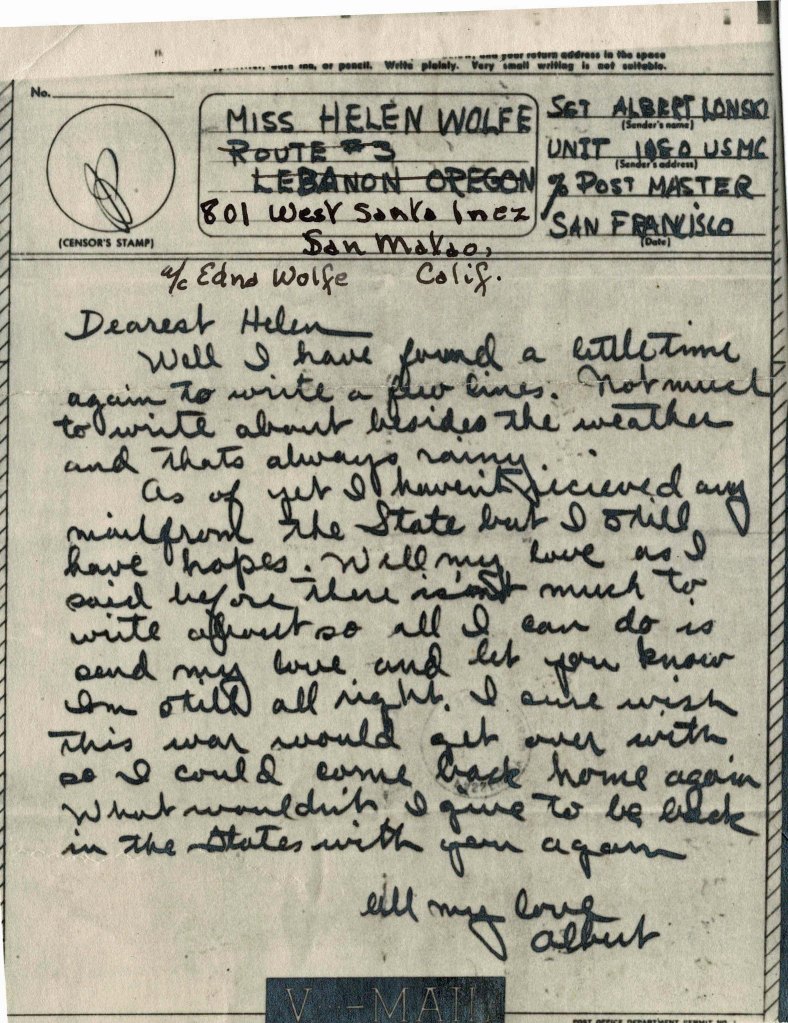

The favorite letter Helen got form Albert reads.

Dearest Helen,

Again, I find a few minutes to write you a few lines of my troubles. For the last couple of days it has been raining so much that we almost have to swim to and from our tents. The water is about 6 inches deep around our tent now and it is still raining. Oh, what I would do for a little bit of that California sunshine and a little bit of that moonlight with you. It's been 5 months since we left San Diego that November day and I haven't been with you, my love since that June day in Brawley, remember? I wish they would hurry up and finish this damn war so I could go back home to peace and quiet with you again.

By the way, I still think of you all the time and miss you very much.

This is a tropical hell hole without you; if you were here, it would be a paradise, my love.

I love you,

Albert

Helen Goes to the European Front

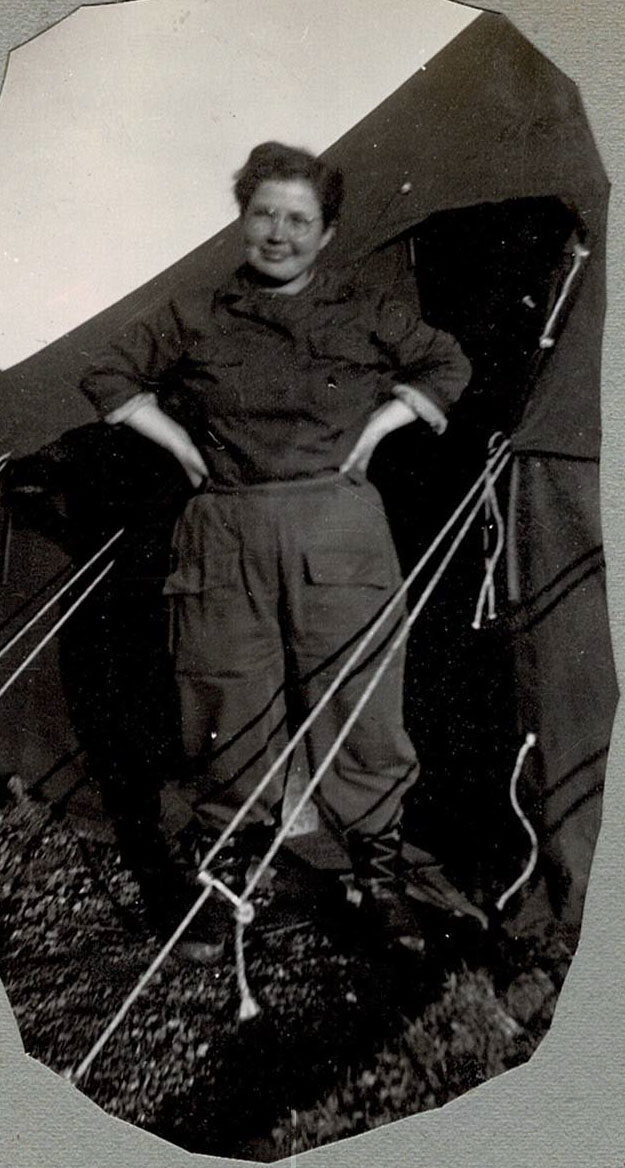

One reason Helen enlisted in the military was she hoping to be stationed close to Albert. She received basic training at Camp White in Oregon. She started here on January 13, 1944. On January 10, 1944, she became an army nurse and 2nd lieutenant. She saw duty in France, Le Mans and Charters. She arrived somewhere in England aboard the hospital ship, named Charles A Stafford in September of 1944.

The journey from England to Normandy was difficult.

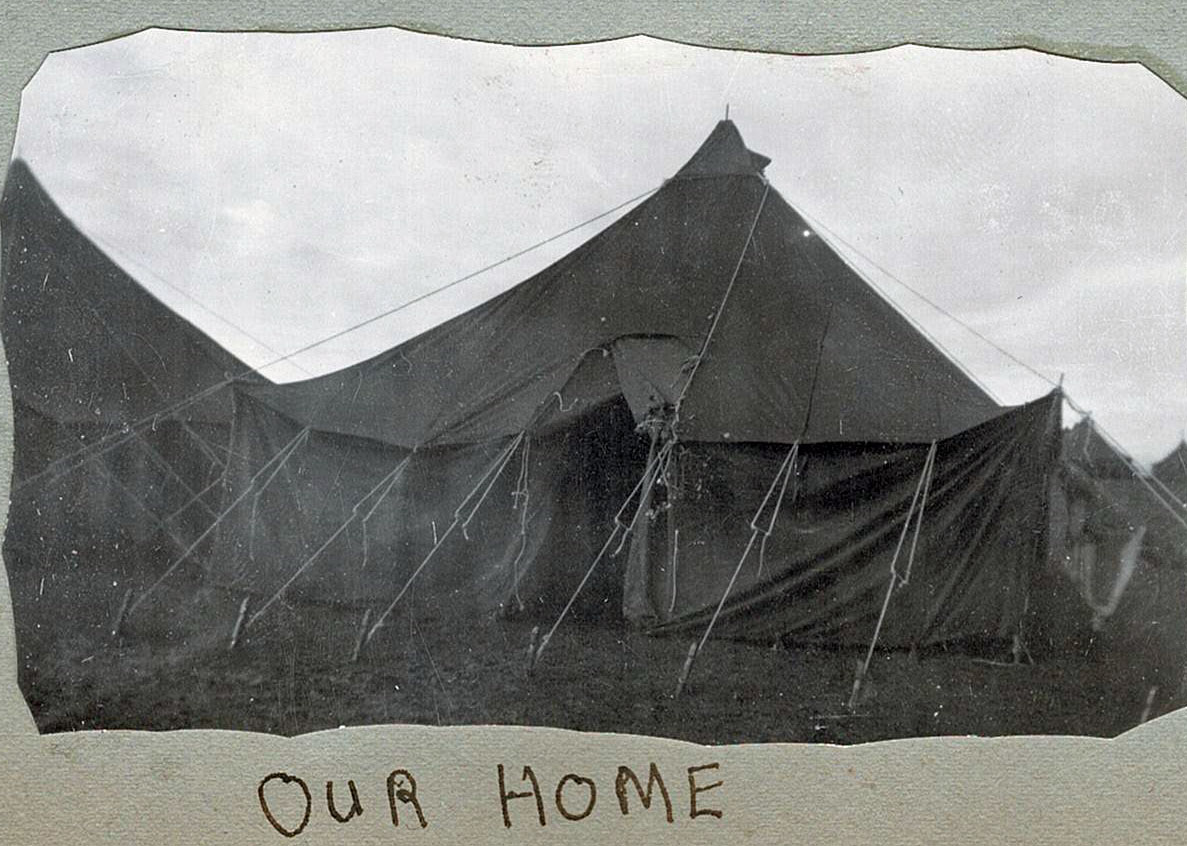

The Tent Hospital

This 1,000-bed tented hospital functioned as an Allied Military hospital. It operated between November 21, 1944, and April 5, 1945. After the April date Allied patients were transferred to other hospitals. The first few months at 170th General Hospital located near Le Mans, Normandy, France were cold, wet and uncomfortable. Helen arrived with the 83 nurses assigned to this hospital on November 13, 1944.

Here is a description of early camp conditions from the WW2 US Medical Research Centre- Unit Histories- 170th General Hospital. The quoted information is from the Improvisation, procedures, equipment, manpower section.

170th General- Le Mans, France

Improvisations had to be made for the lack of certain equipment. Lamps were manufactured out of bottles filled with kerosene. Much borrowing from neighboring units had to be done to keep life from being miserable. The TAT (To-Accompany-Troops) equipment was hauled to the hospital site from the railway station.

On 21 November, 404 patients were admitted, and there were still no ambulances for disposition and evacuation, the water supply was not yet declared potable, and electric lights were not yet installed. The coal allotment for December had been hauled in, and tents, stoves, and beds set up.

Soon after the Hospital opened, a PW (Prisoner of War) enclosure was built, and before Christmas 250 German PWs and 28 French civilians were working in the Hospital Plant. It would not have been possible to efficiently run a hospital of this size with such a low T/O of personnel(T/O is short for Table of Organization and referred to a specified number of personnel). Forty (40) EM Enlisted Men) were tasked with guard duty alone. The 170th General Hospital had been operating under canvas since it opened on 21 November 1944, with the help of borrowed tentage.

Unfortunately, only 8 wards had been winterized, and it took another three weeks before winterization of all the wards was completed. Stoves and fuel were now available, but there was no electricity. The unit managed to borrow one 30 KW (kilowatt) generator from the 19th General Hospitaland, after about two weeks, Engineers installed two of their own generators. No canvas repair kits were available, and as of 31 December, it was impossible to repair leaking tents. Lumber was missing, GC (Geneva Convention) Red Cross markers were nowhere to find, red and white paint was not made available. Circulating pumps could not be obtained, and therefore only one shower unit could be installed for the patients.The hospital staff had no accessible bathing facilities for three- and one-half months. The water was obtained from a 200-foot well on the grounds, and a concrete underground water tank of 15,000-gallon capacity served as the main storage tank. Individual washing was done by everyone, and there was no dry cleaning in the neighborhood. Everyone slept in his clothes, as it was too cold to undress without fires.

Nurses had to keep wearing their class A uniforms, and had no sweaters, no leggings, no overshoes, other people missed overcoats, raincoats, and had no extra clothing. Luckily some extra combat clothing had been obtained on 7 November. Messing was improved after receiving ranges, but keeping food warm remained a problem, and the lack of certain items such as salt and pepper shakers and coffee cups caused problems when serving bed patients. There was a shortage of stovepipes, and there were insufficient personnel to operate everything, so, 60 PWs were employed in the three messes to help serve 1,500 to 1,600 people three meals a day. There was no concrete slab on the floors, no drainage gutters were provided, and dish washing facilities were totally inadequate …

Around this time Helen and her tent mates had a run in with General George Patton. This is what Helen said about this meeting.

A Chance Meeting With General George Patton

Into our tent stamped a big bluff man with general bars on his shoulders. He was yelling, “what is all that female underwear doing in my command, 3 miles from the front.” We (the army nurses) had saved rainwater in our helmets and some drinking water with which we washed our panties and brassieres in our helmets. Then we hung them with large safety pins from the outside tent ropes. These items were dancing in the breeze. They were all different colors, and I thought they looked interesting, but not military. It did show women lived here and women determined to keep clean.

He hooked a thumb at me. “Where is she going all dressed up?”

We did have our good uniforms in our bed rolls. I had been invited for a dinner and a shower at the navy outfit camped on the still mined Utah beach.

He yelled, “Get a fence up with clothes lines and hide that female underwear. I don’t like the Navy washing our Army girls.”

I went to a shower and good dinner at the Navy camp. He stomped away yelling, “Female underwear 3 miles from the front.” But in a soft low voice I heard, “They are certainly pretty.”

We had good showers the next day.

By the end of November living conditions were better. Helen sent this letter to her Aunt Sigrid telling her about camp life. This was a little before they cared for many patients.

4 Nov 1944

Dear Aunt Sigrid & Maudie,

We’re still in our cow pasture. We’re quite comfortable now. All in getting used to it, I guess. I don’t wear all that extra clothing I did at first.

Hope you’re not working too hard. I ‘m, not yet.

I’m staying home tonight trying to write some letters.

There seem to be always some plan to go out such as it is. We ate steaks the other night. We’re getting stubborn and won’t go out unless they feed us.

I’m trying to write and talk at the same time.

We don’t do anything but a little drilling now and then. We have our bed rolls now and are warm enough. We’re sort of acclimated now too, so I don’t wear so many clothes around. In fact, I go to bed wearing only one pair of flannel pajamas.

Would you send me some calcium tablets. We don’t get milk, and my nails are getting brittle, we get good food now though.

Love, Helen

The End of the War

V-E Day, May 7, 1945, saw the end of the war in Europe. Helen wrote a poem.

No War Now

Listen to the silence.

Hear the quiet.

Feel the mystic moon sighing.

Now, there is no crying

Tonight. The World is at peace.

on January 1, 1946 Helen traveled to camp Philip Morris. This was a large Army staging camp near the port of Le Havre, France. From here she returned to Presidio of San Francisco near San Mateo in the United States.

Helen and Albert

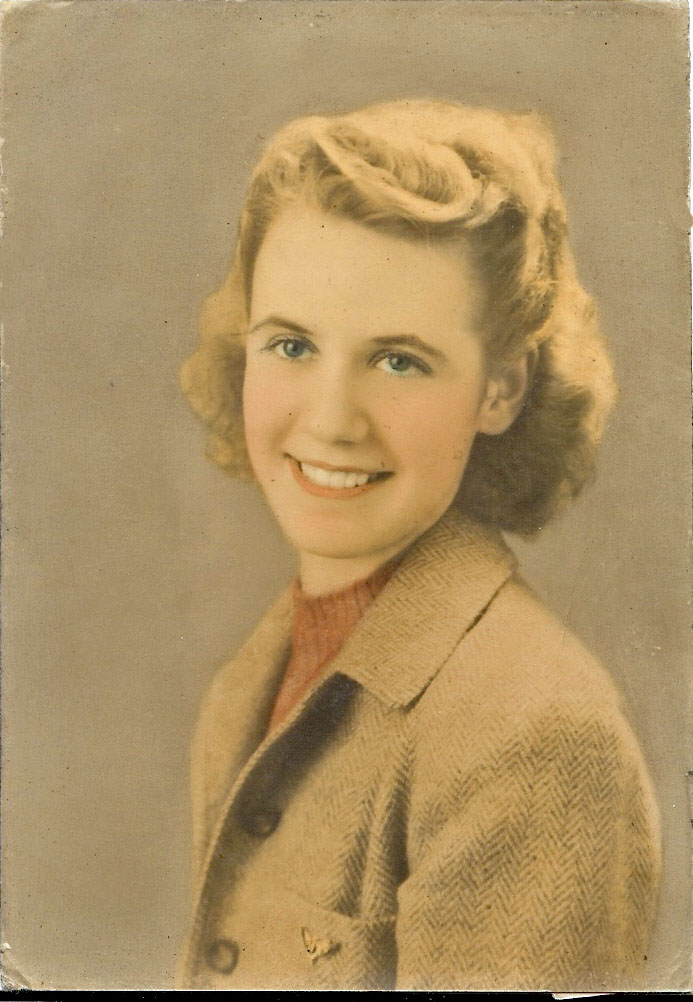

Albert was already out of the service. He had separated from the United States Marine Corp in September of 1945. He attended engineering classes at the University of Washington in Seattle. In February of 1946, he visited Helen in San Mateo. They married on February 26, 1946, in Burlingame. Here is Helen’s wedding photo.

Helen wrote two poems about love.

Pulse of Independence

Two hearts ought not to beat as one.

For if one stops,

The other stops too.

They should beat alone

So, when lying close

They do not sing a single note,

But together they play a melody.

Circles

Love is not pie

To be divided

And slices given

To friends and relatives.

My love for you

Is a full 360 degrees

That encircles you,

Front back and sideways.

You cannot turn away from it.

And if I choose

To love a few hundred other people,

It takes nothing away from you.

For my love is expandable.

Helen’s mother and aunts in Lebanon, Oregon honored the new couple with a reception in the spring of 1946. Helen wore the dress a German prisoner of war had sewn for her in France. This tailor fashioned the dress from a white silk parachute.

Old Marrieds

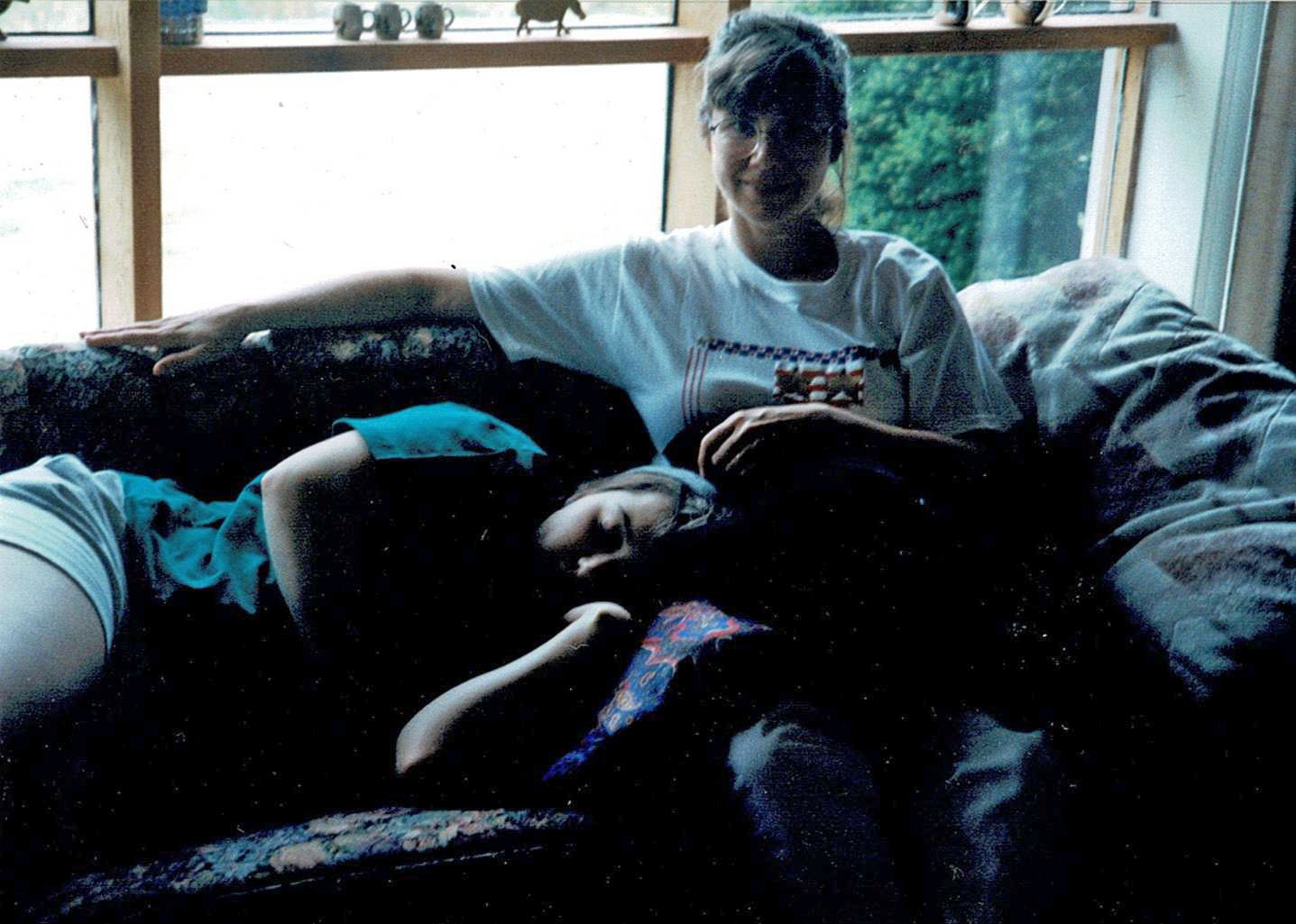

Here is a photo of Helen and Albert taken in 1980. Their last abode was at 33063 Berlin Road, Lebanon, Oregon.

I wrote a poem about them at this time in their lives.

Old Marrieds

By Jill Foster

The old man builds with rock, wood and colored glass

Drawing his projects before.

The old woman plants her gardens

With trillium, dog tooth violets and abandon,

Sowing her seeds freely.

Th old man gives great, lavish gifts

Planning months ahead.

The old woman sprinkles presents about

Buying books for any child she knows.

Giving tidbits of home cooked treats to stray pets and people

And kind words all around.

The old man loves with his hands and eyes,

Touching and looking his feelings

Saving his words.

The old woman gives volumes,

Poems, postcards, letters,

Using words to create gentle bonds

And insightful meanings.

These two bound together by choice

Apart in their ways, stand together

Making their world

A little better.