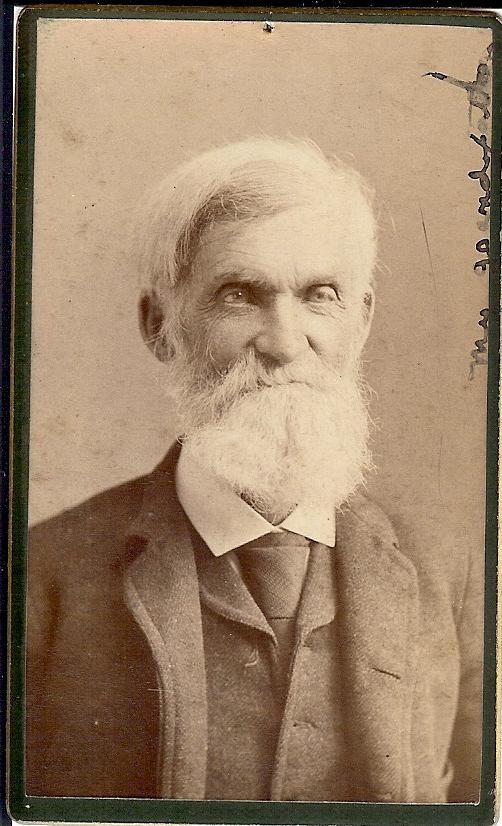

As the son of a Virginian plantation owner with the American Civil War approaching, John B. Cabell grew up with privilege and tension. The plantation, Green Hill, sat on a high grassy hill overlooking the James River. The county where they lived, Buckingham, was in the very center of Virginia. Their plantation came with 750 acres and enslaved workers. John’s father, Louis Cabell, had inherited all this in 1841 from his father.

Alexander Brown, a Cabell on his mother’s side, wrote an informative book about this family. The Cabells and Their Kin states John Breckenridge Cabell drew his first breath on January 26, 1850.

Louis W. Cabell and Anna Maria Perkins Cabell named this son John Breckenridge Cabell after the 14th Vice President of the United States. John Cabell Breckinridge, shared second great grandparents with Louis and Anna’s new son. These 2nd great grandparents were Elizabeth Burks Cabell and William Cabell, M.D.

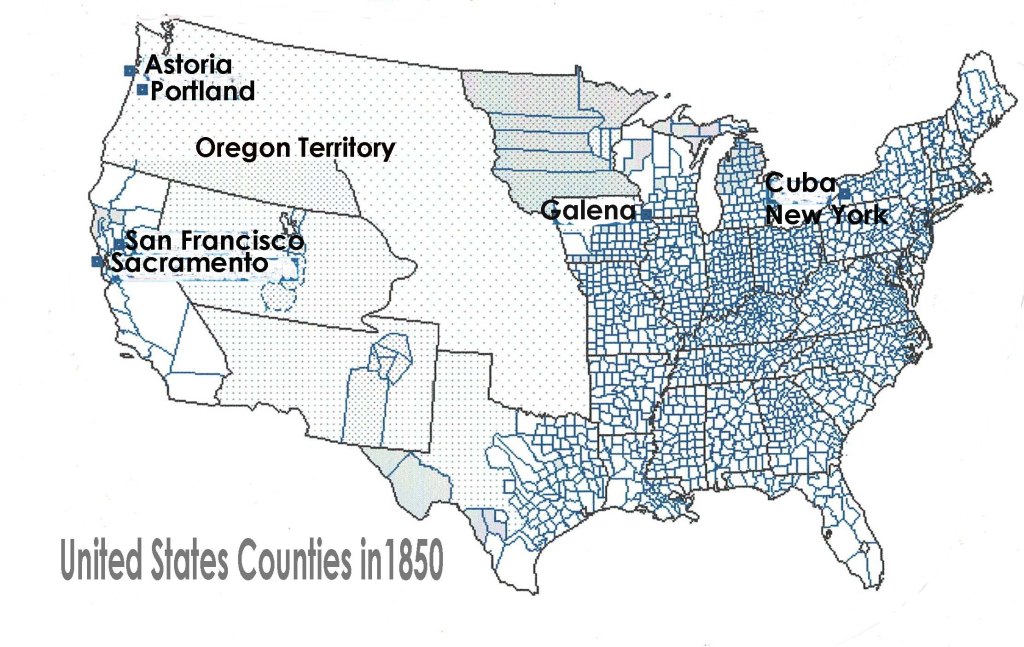

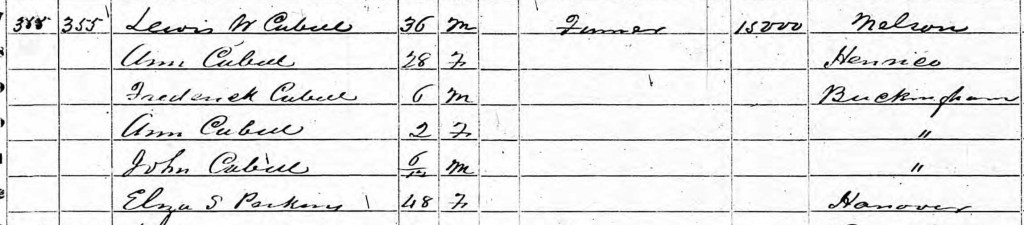

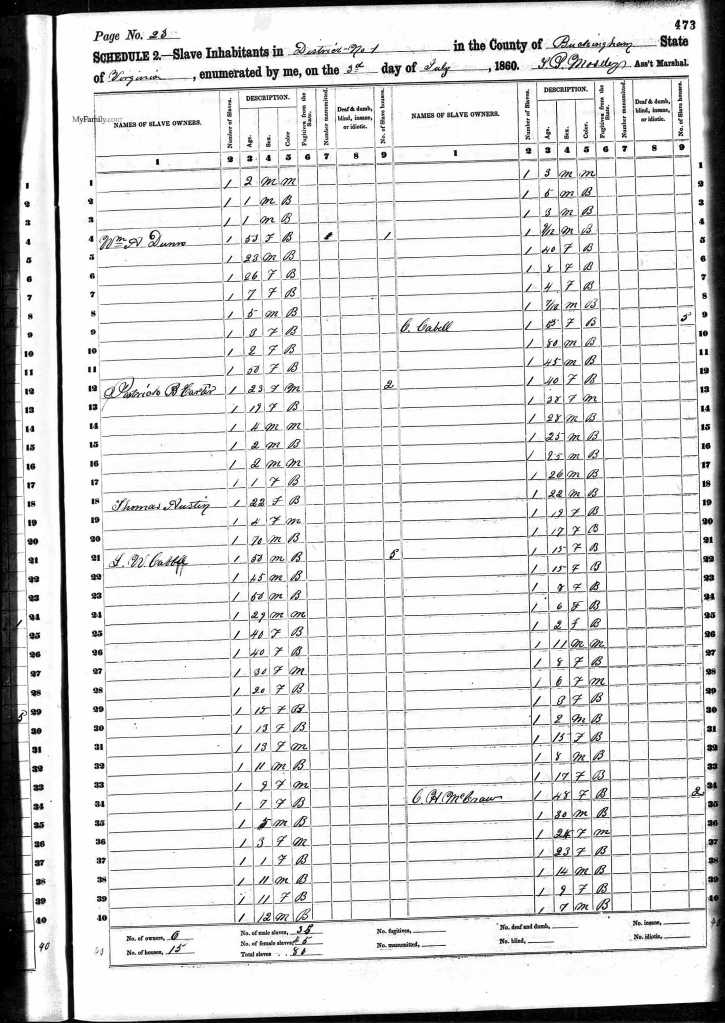

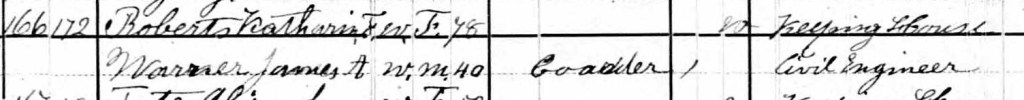

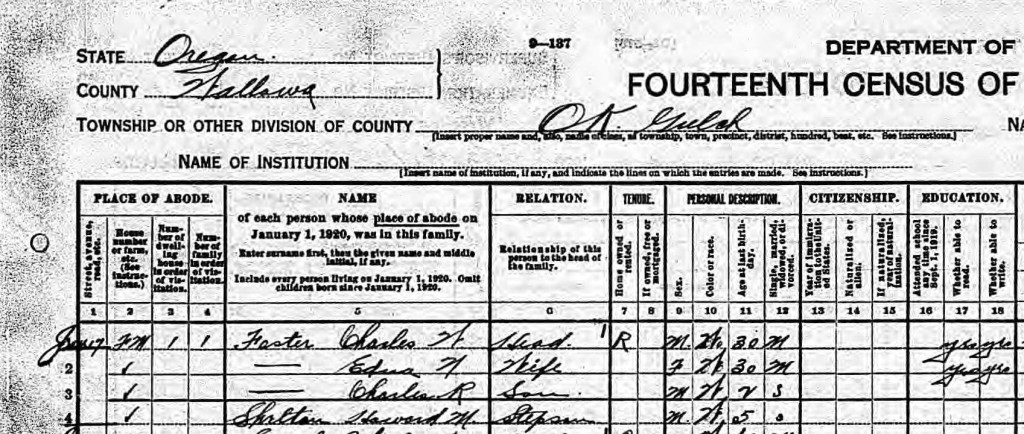

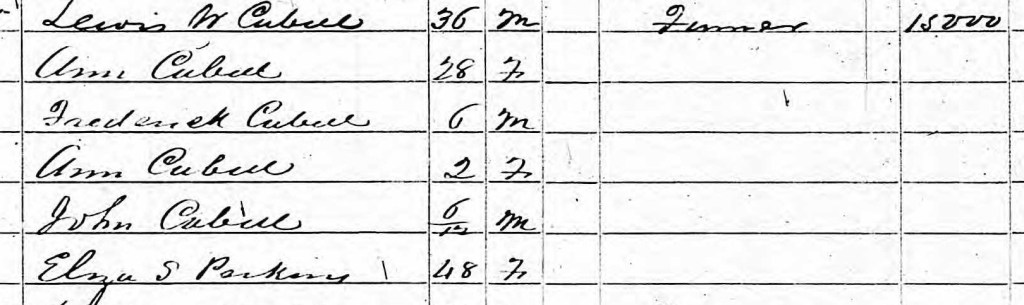

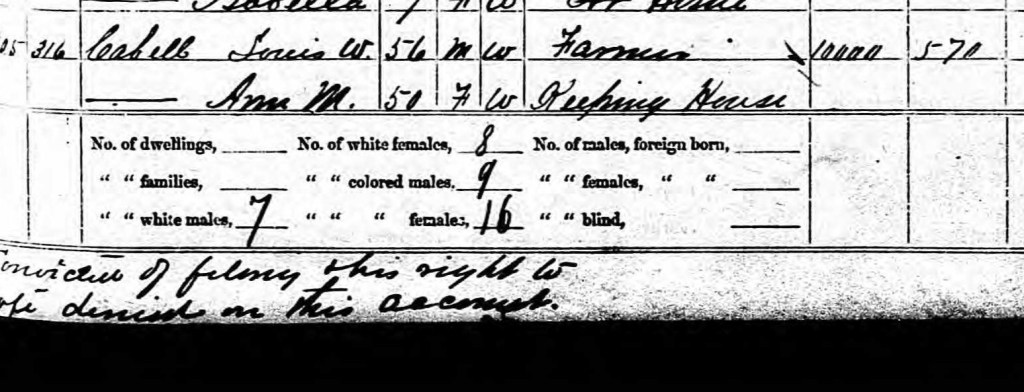

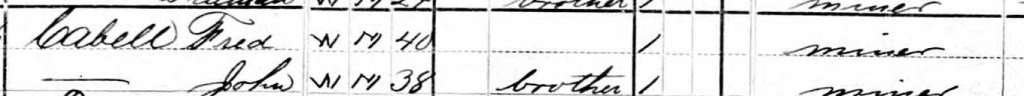

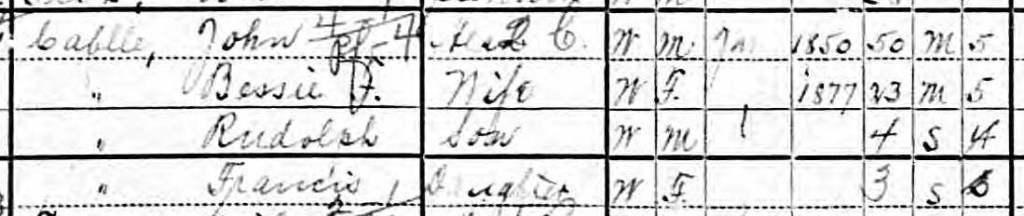

The 1850 Census Record

Enumerators for the 1850 U.S. federal census named all the persons living in each “dwelling” they visited. This was a first. The enumerator also recorded the ages of those they visited. This proved to be useful in John’s case as later records suggest that he was younger. In 1850 John’s age, listed as 6 months, would make John born in early 1850. The census visit happened in Buckingham on August of 1850.

This is the first census secret in John’s record. It revealed his birth year as 1850 unlike his death certificate which listed his birth as January of 1851. This early census record shows he was very much alive in 1850.

Here is an image of this record.

Between Census Records

Stories from John’s daughter, Frances Cabell Coursen Perritt, say John’s father, Louis W. Cabell was demanding, temperamental man who caused his wife much grief. After John married Bessie Reynolds, John’s family and Bessie wrote letters to each other. A cousin of John, Clara Lee Horsley, wrote on April 9, 1932. She described some of John’s early life.

Clara said John’s father, Louis, was erratic. He would call John a bright shining lamp, with a beautiful face and brown eyes like his mother. Then he would turn around and say Johnny Breck is the Black Prince.

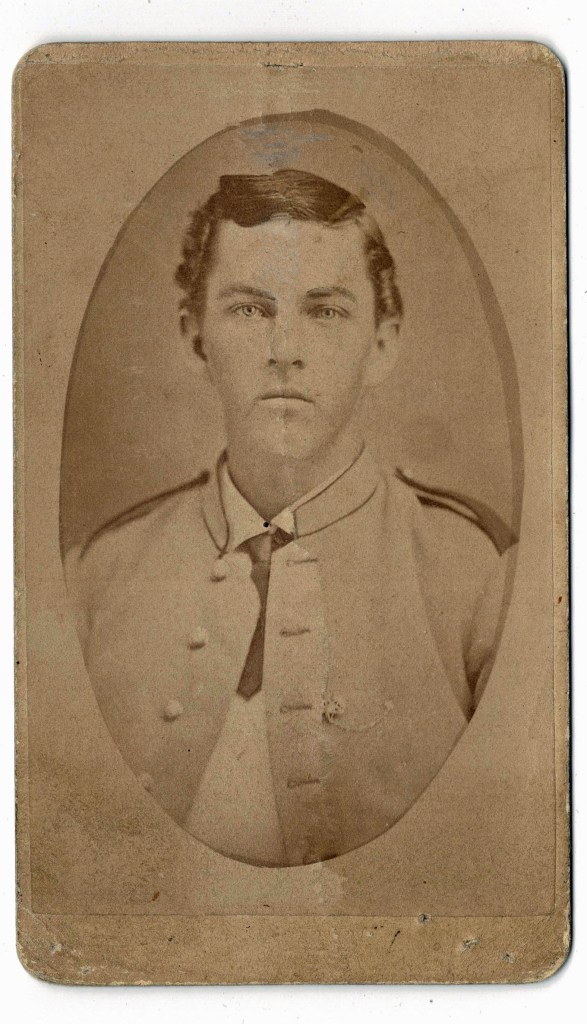

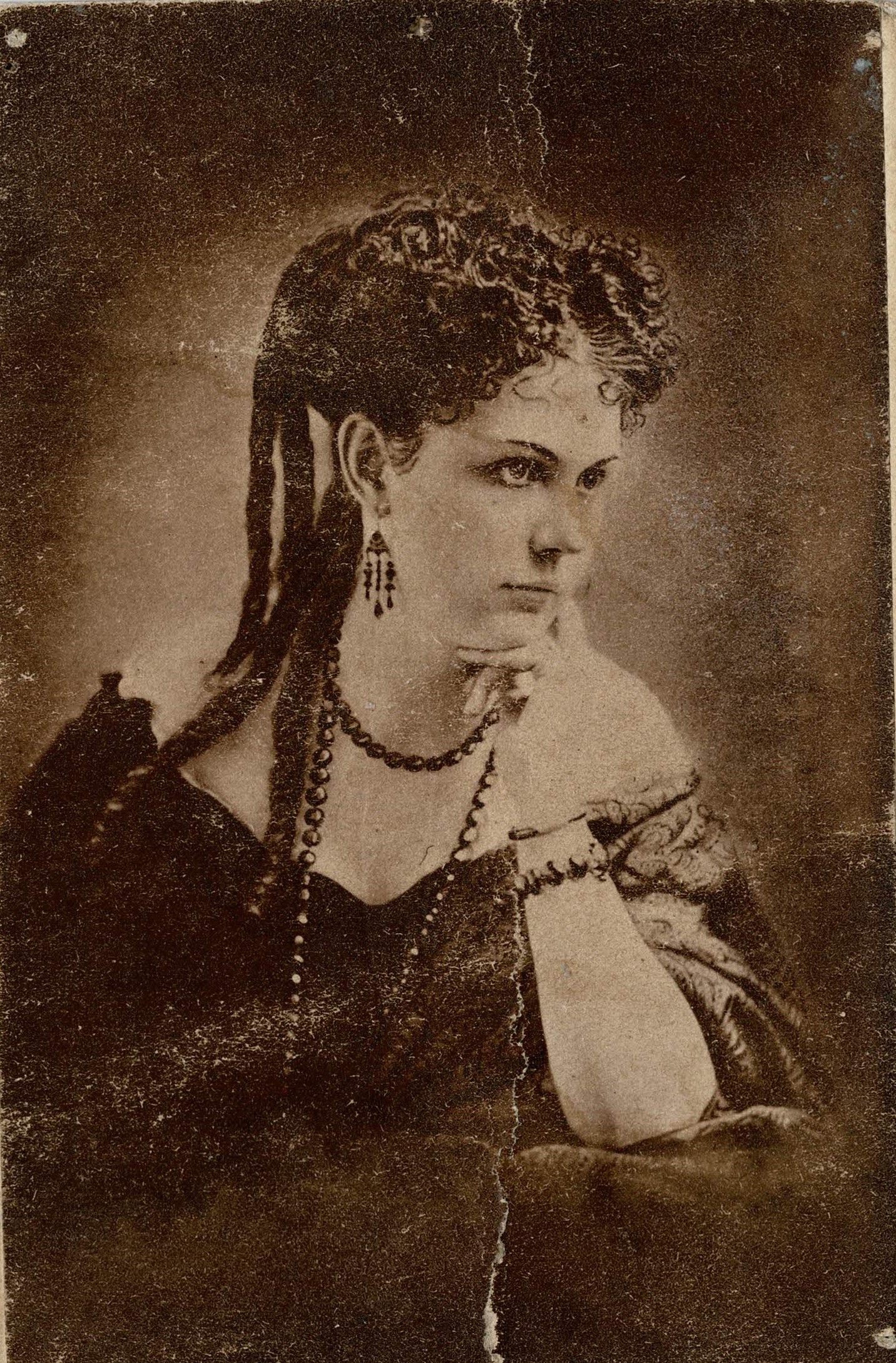

In this letter Clara mentioned two friends of the young John Cabell. She wrote J.B., Jessie Cabell and Susie Campbell made a handsome trio. She mentioned some photos taken before John went west.

Times Are Changing

Virginia’s economy relied on slavery to support the lifestyle of the plantation owners like John’s father. In the Slave states white man called the practice of slavery their “peculiar institution”. In the North the idea of a person being the property of another person was fast becoming horrific.

The Cabells, like the other owners living along the James River, felt this way. Secession would be their only choice if slavery was abolished. They especially felt this way after the election of Abraham Lincoln in November of 1860.

The 1860 election campaign brought Abraham Lincoln into the office of President of the United States. Lincoln had said he would not allow slavery anywhere in the country except where it already existed. Southerners wanted to take their enslaved into the territories.

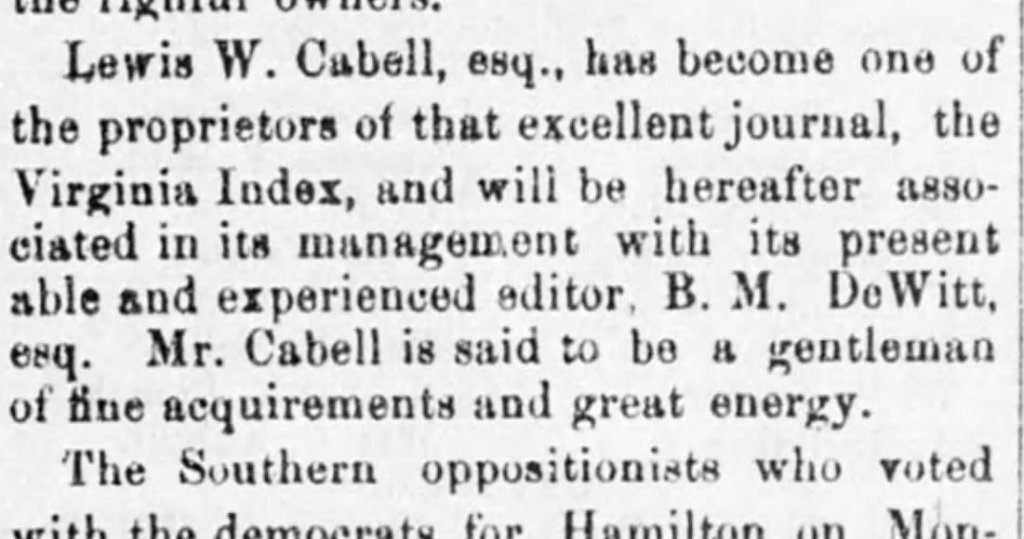

At this time John’s father owned the Virginia Index, a Richmond newspaper. An opinion piece, published on October 12, 1860, stated the slave state position. Part of the article reads, from the time of the nomination of Lincoln it was proclaimed by Southern Politicians…that his election would justify and lead to a dissolution of the Union.

It went on to say their enslaved Negroes were property like horses, cows and liquor were property. The people of the slave states wanted protection of their property from the government which demanded their allegiance. They did not want denial of their property rights in the territories. Here is a link to that article.

The November of 1860, the election of Lincoln spurred more drastic measures in the Cabell household.

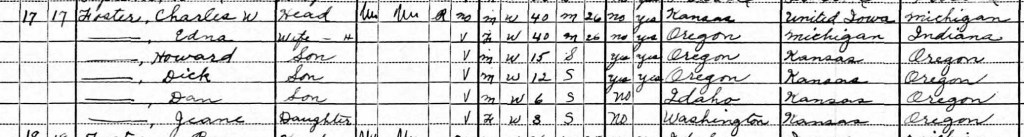

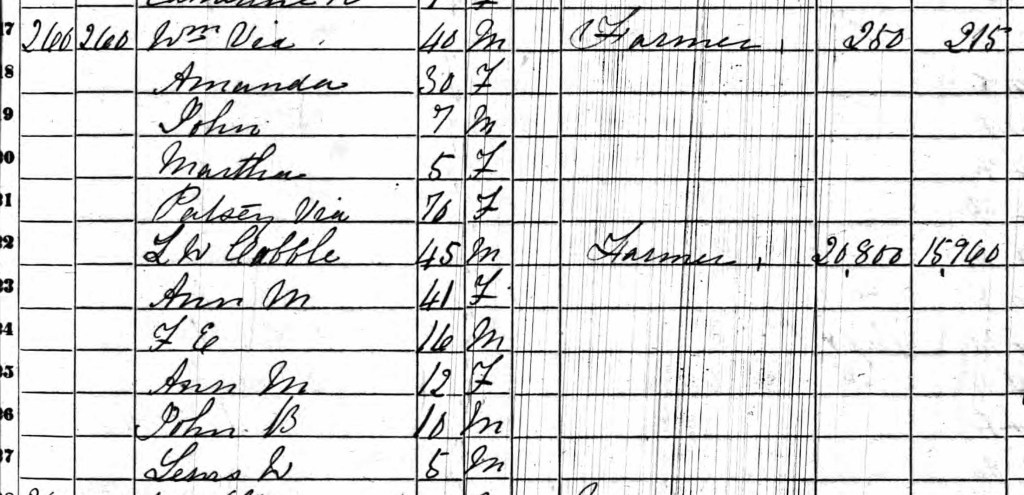

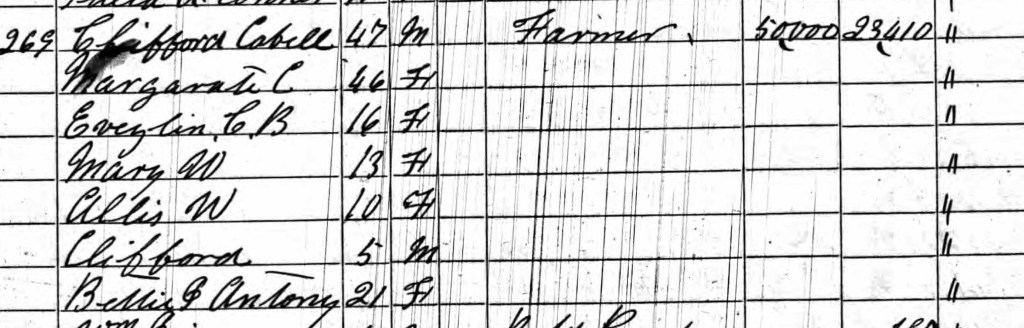

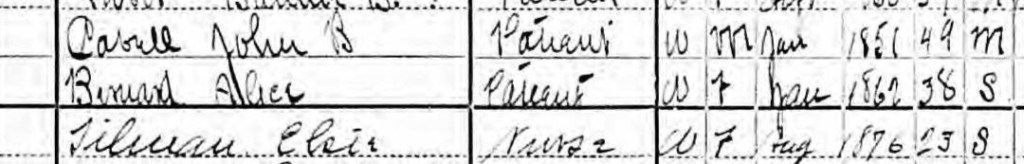

1860 Buckingham Census

On July 6, 1860, when the Buckingham County census enumerator called at Green Hill, the Cabells were not there. The census taker found them living in dwelling number 260 with the William Via family.

In this record Cabell is spelled Cabble and initials are used first and middle name for Louis Warrington Cabell.

John’s age, 10 years, coordinates with the 6-month age given in the 1850 record.

Louis Cabell’s brother Clifford Cabell is in dwelling number 269. Clifford Cabell’s daughter, Evelyn Carter Byrd Cabell, was someone John kept in touch with after he went west.

The Civil War in Virginia

Green Hill, the Louis Cabell Plantation home, served as a recovery hospital for Confederate soldiers. The war began about 8 months after the 1860 census was taken. It started on April 12, 1861, at Fort Sumter, South Carolina. John was 11 years old and too young to enlist. John’s older brother Frederick Cabell enlisted. Frederick fought on the Confederate side from the beginning until May of 1865 when the war ended.

The Confederate capital in Richmond was about 100 miles from Washington, DC. Virginia saw the most war. According to the National Archives Catalog, Virginians saw 123 battles in their state.

After the War

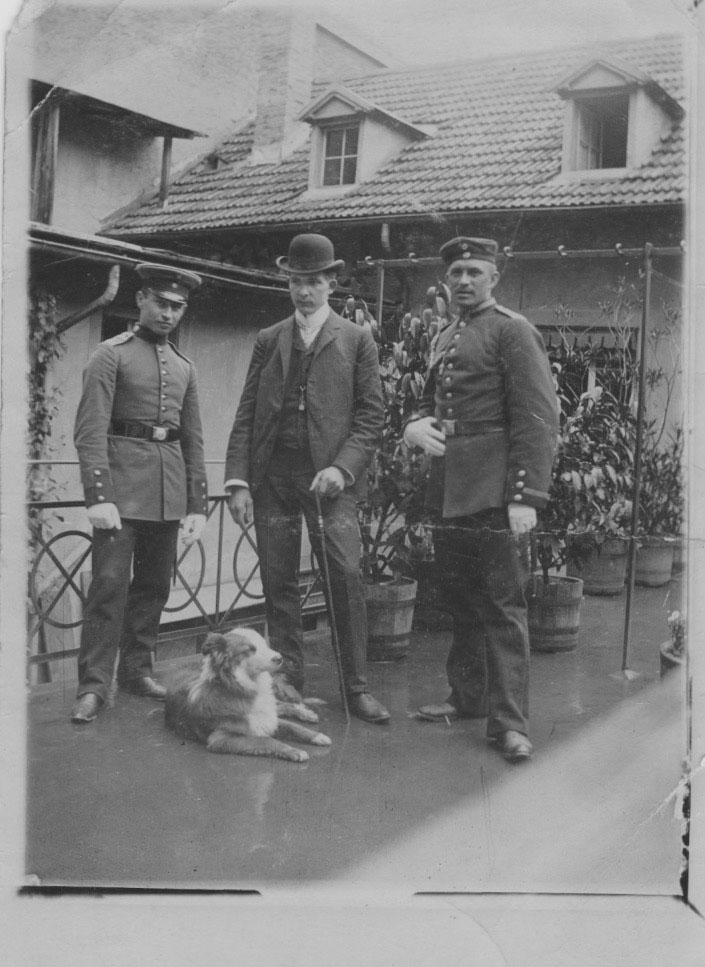

After the war, both John and his older brother, Frederick, pursued higher education. They were both interested in mining engineering. Plantation ownership was becoming a thing of the past. Frederick left the States for Freiburg, Germany where he studied mining engineering. John attended Norwood High School, a boy’s prep school preparing their students to attend the University of Virginia.

In the fall of 1865, one of John’s cousins opened Norwood High School. William Daniel Cabell’s (1834-1904) plantation home, Norwood, became a school for 47 boys.

John went on to attend the University of Virginia. This university offered a program in civil engineering. In the 1870 census record, John is listed as a civil engineer.

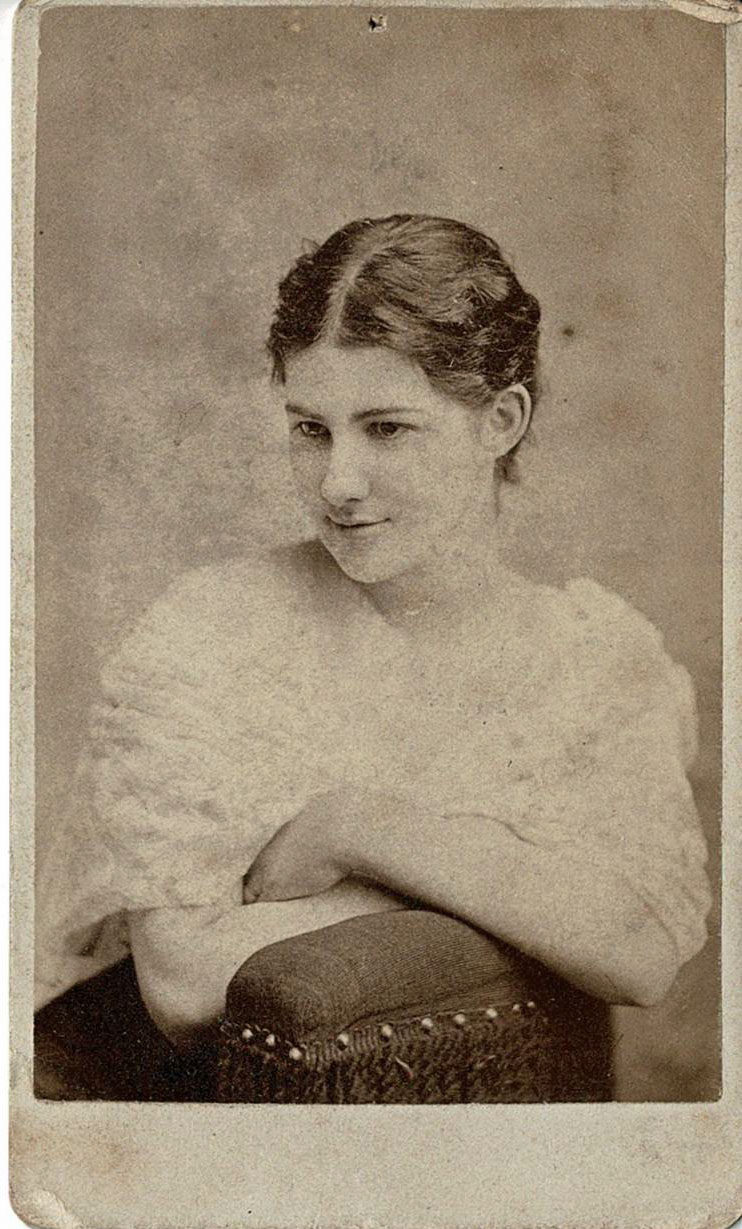

The Beauties in John’s Wallet

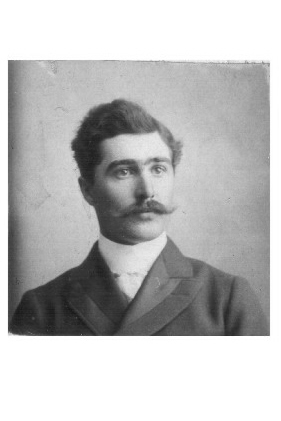

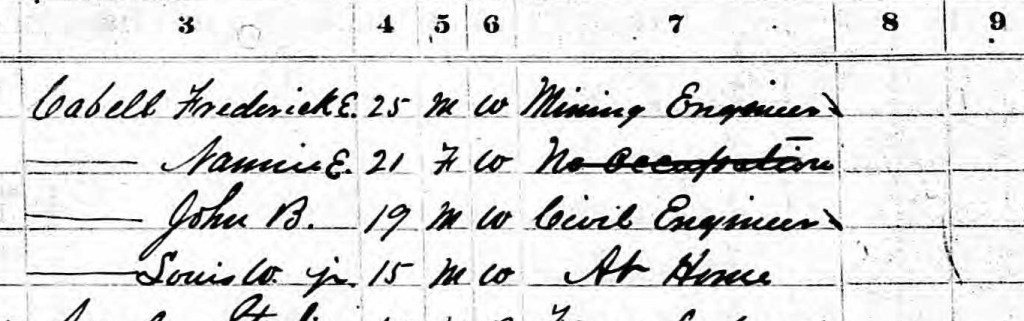

Not long after, John was photographed by George N. Wertz in Christiansburg, Virginia. The photographer, George, had a studio in Christiansburg in 1872 and in 1873. In this photo, John was about 22 years old.

I don’t know if John carried photos in his wallet. But I do have some photos of John’s from his younger days. One is him; the others are girls. They are left to right Ridgie, Miss Susie Campbell, Evelyn Cabell Robinson and a cousin.

John B. Cabell’s 1880 Census Records

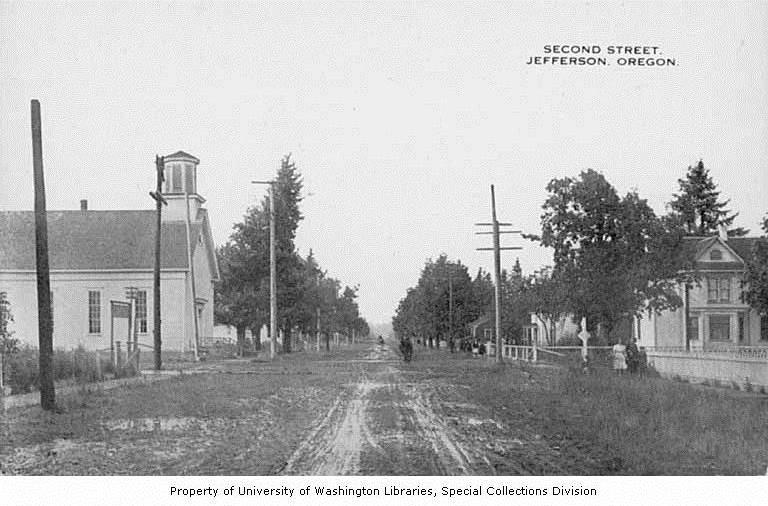

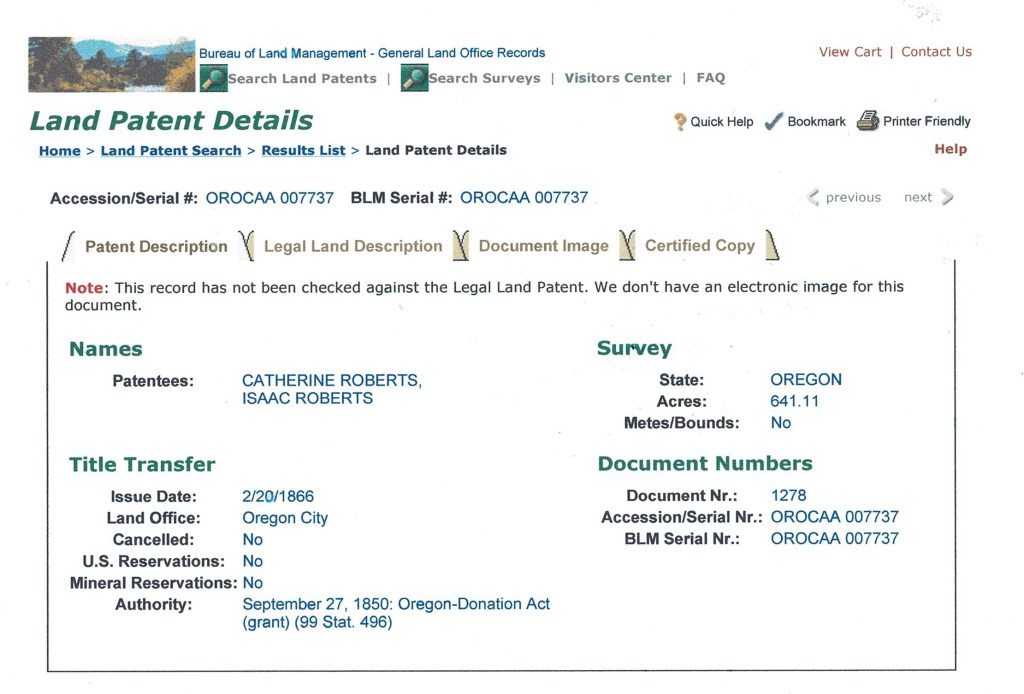

As early as 1873, John B Cabell and his brother Frederick discovered and worked mines in Grant county, Oregon. Here is a link to their mining enterprises in Oregon.

The 1880 census shows them being in Grant county.

Occasionally, John visited Baker City. It was not unusual to find him at the bar in the Geyser Grand Hotel. I don’t know if this next photo taken at this bar predates his falling in love. This is written in the back of this photo, “John B. Cabell, person on the right in front of the bar.”

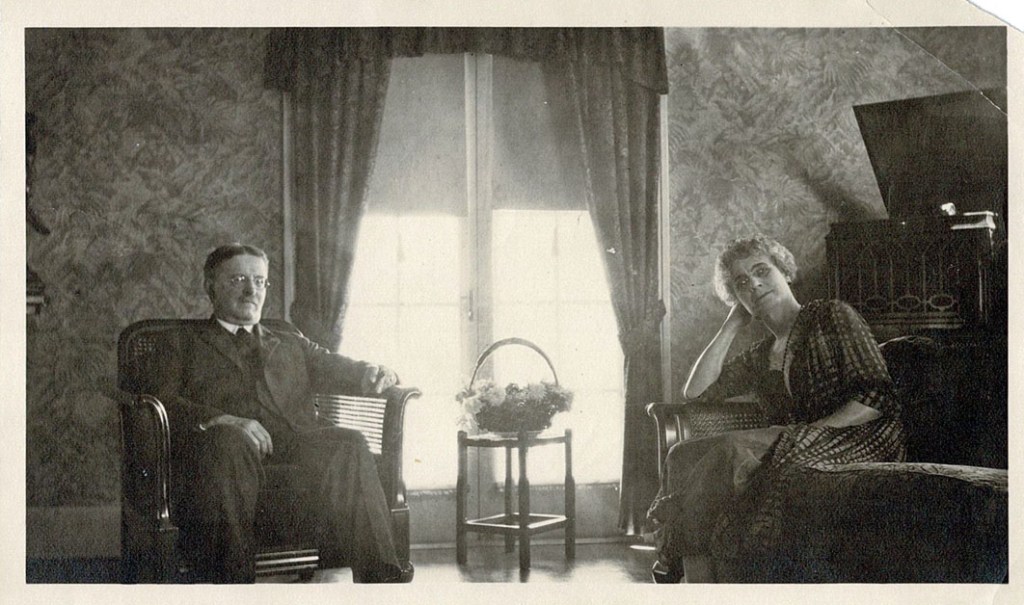

Bessie’s and John’s Story

Another blog entry tells Bessie and John’s love story. Here is a link to In the Beginning.

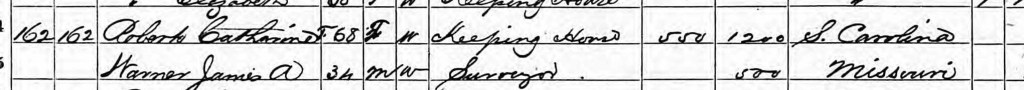

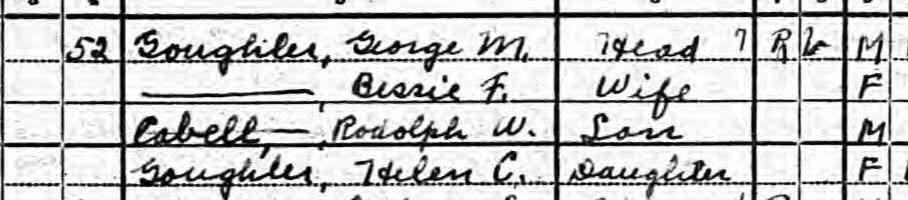

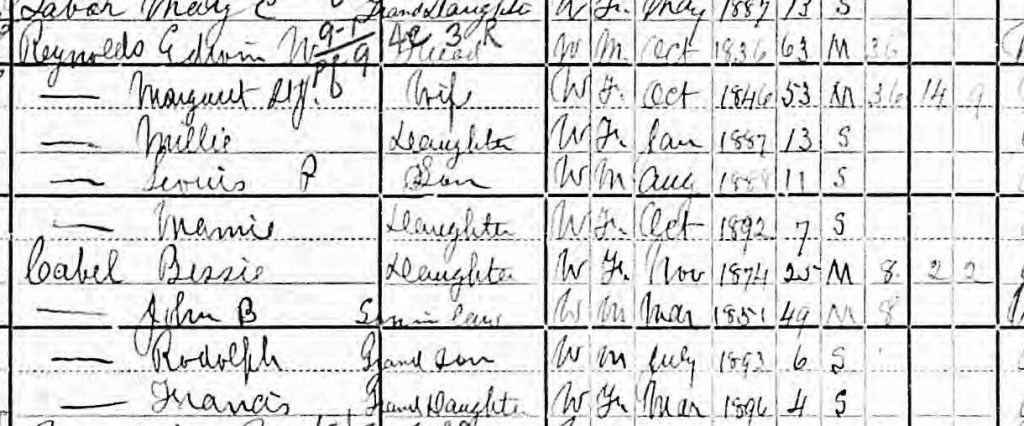

1900 Census Records

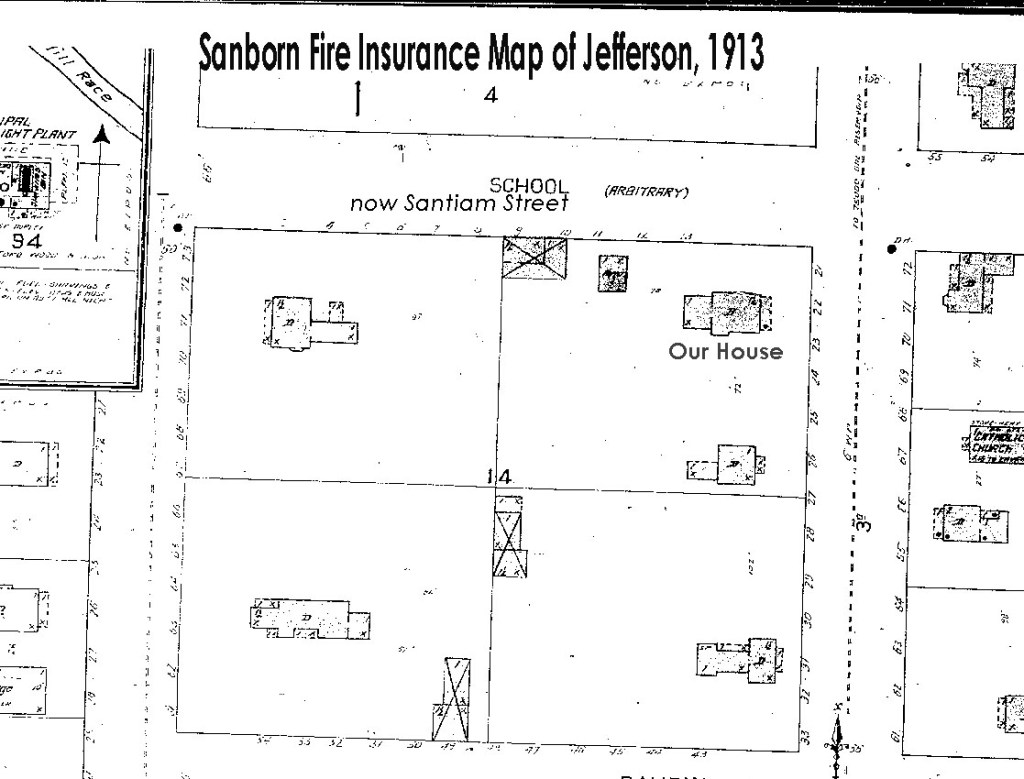

Interestingly, John is listed in three 1900 Oregon census records. The first time John B. Cabell was counted in the 1900 US census record for Oregon. He was a patient at the Portland Sanitarium in Portland, Oregon. This was on 14 June 1900.

A few days later, he went home stopping first in Baker City to get his wife and children. They were living with his wife’s parents Edwin and Margaret Reynolds. This was 18 June 1900.

John’s Last Census Record

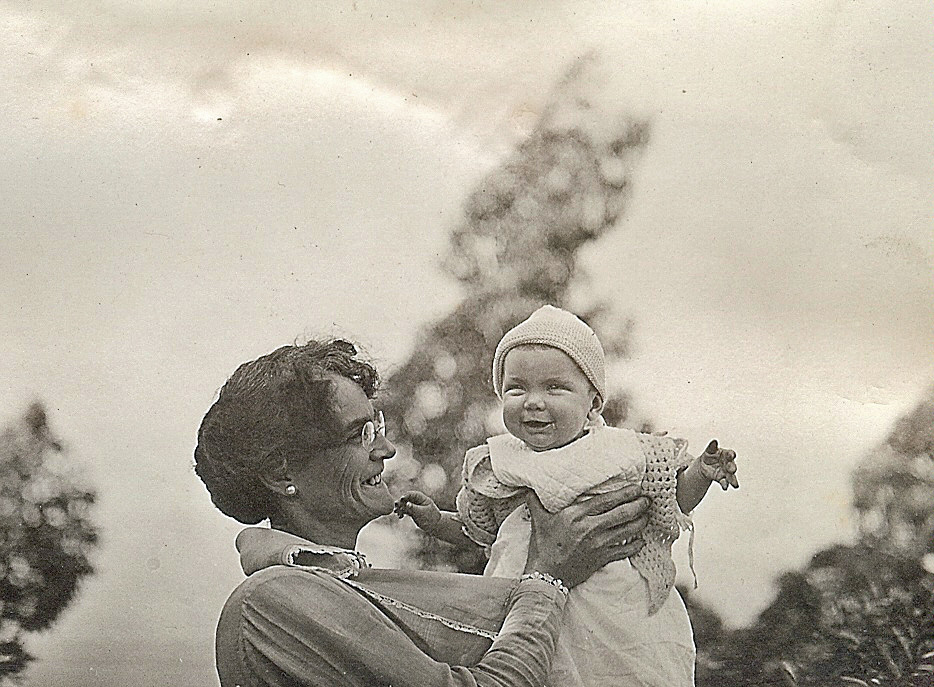

The family returned to their home on a mountain above Granite City, Grant, Oregon. They were counted here on 20 June 1900.

Being counted 3 times in a census record seems excessive. John had trained as a civil engineer who concerned himself with numbers. He know the purpose of the census was to make a true count of the population of the U.S. More important to him was the reality that he had moved home. This was where he wanted to be counted.

Even though the triple counting of John affected the accuracy of the 1900 census, it still supplied information about John. This last 1900 record listed his correct age. John was born in January of 1850.

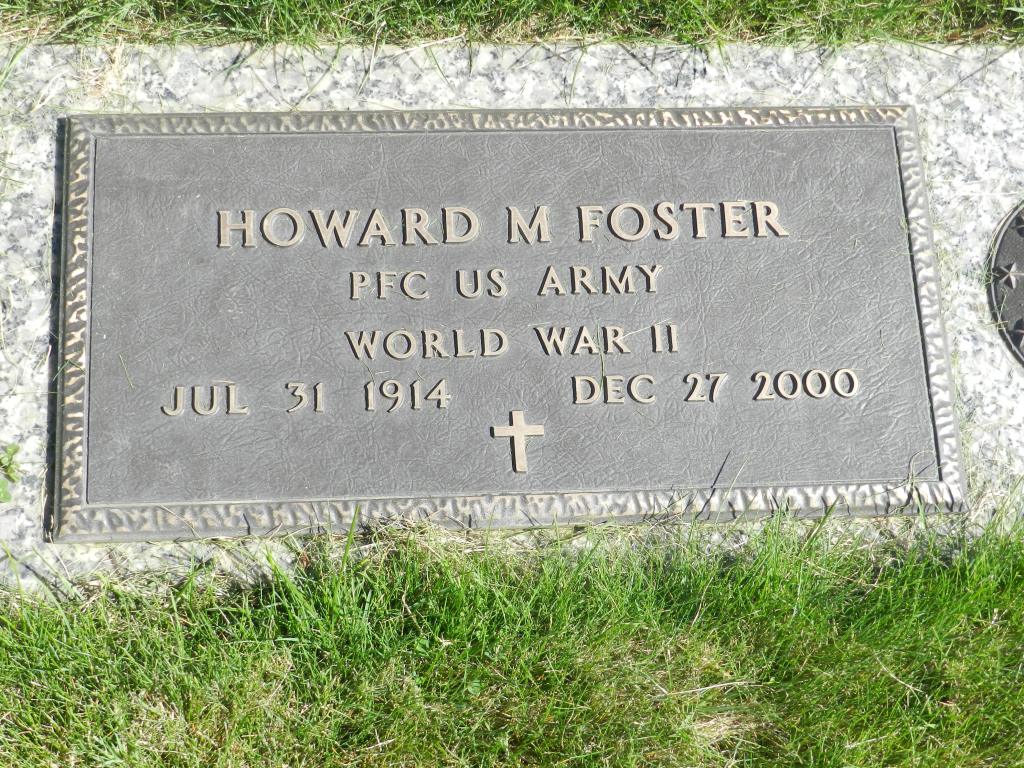

Sadly, John died a little more than a year later on September 6, 1901 in Portland.

After Thoughts

John is the great grandfather of my husband. I have letters and stories saved by John’s daughter, Frances. Without these treasures, John’s census records would have stumped me.