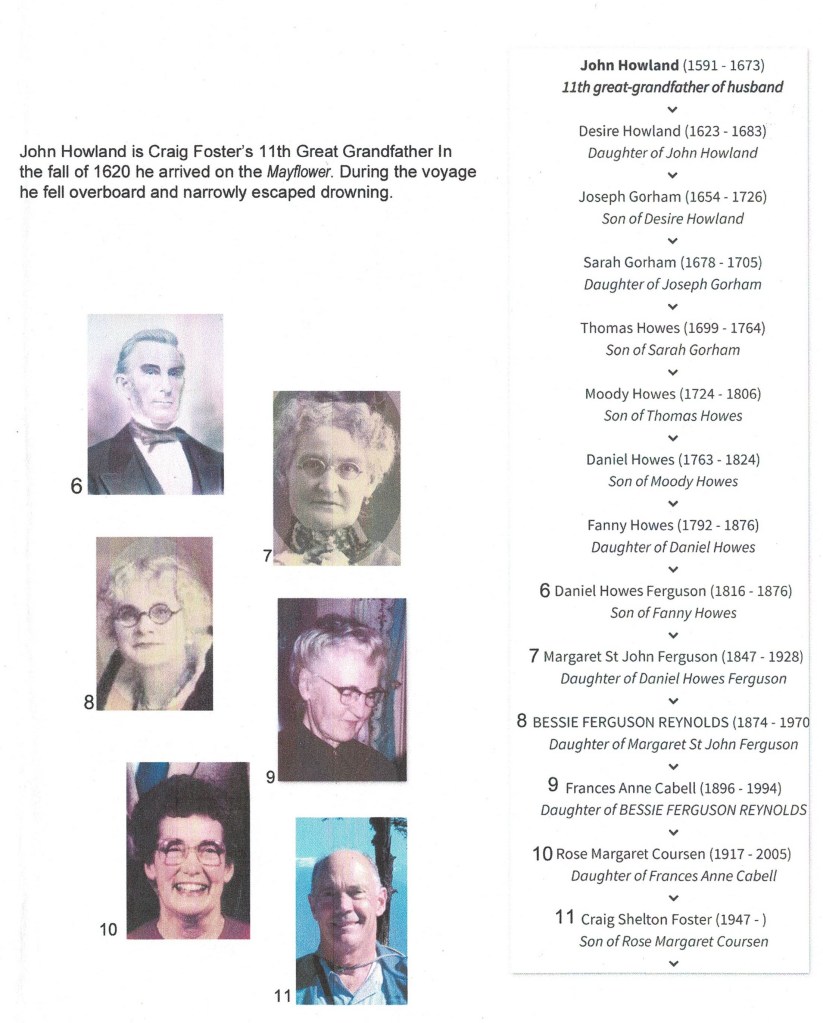

Week 43 Urban, Part 2 of the Daniel H. Ferguson Story

Jeannette Keeler was a city girl. She was born on July 16, 1816, to Abraham Keller and Sarah Dann Keeler. Their town, Danbury, Connecticut, was a growing town of 3.5 thousand people and a thriving industry. The people of Danbury made hats.

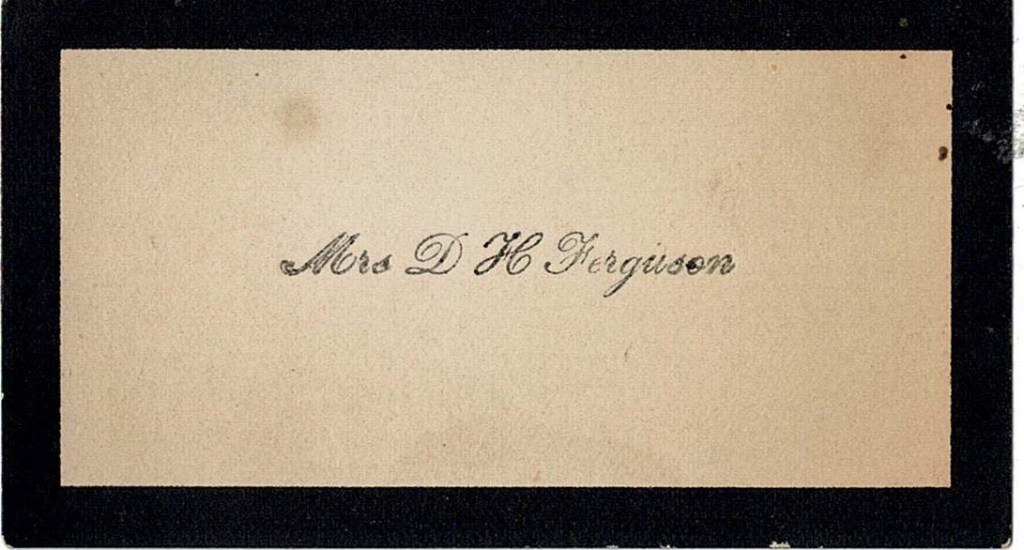

I found a small item from Jeannette’s life in the scrapbook I inherited from my husband’s grandmother, Frances Perritt. Jeannette was my husband’s 3rd great grandmother. This item was a small white card rimmed in black and inscribed, Mrs. D. H. Ferguson. Calling cards or visiting cards, popular across America throughout the 1800s. Ladies carried in small purses when making their social calls to family and friends. They left cards at each house they visited. They usually left three cards- one for the master and two for the mistress. The host often displayed these cards on a small table in the front hall. The card of the most high-ranking caller was on top. A black-edged card meant the caller was in mourning.

Jeannette Keeler married Daniel Howes Ferguson on June 21, 1838, in Danbury, Fairfield, Connecticut. The wedding was a home wedding. J. G. Collum officiated. The young couple settled in Norwalk- a settlement on the northern shore of Long Island Sound. Their five children were all born here in Norwalk, Fairfield County, Connecticut. Their youngest two, both James and Margaret, told census takers they were born in New York. By this they meant the New York metropolitan area which included the city and suburbs of New York City. Long Island where Norwalk, Connecticut is located is in this metropolitan area as well as parts of New Jersey and Pennsylvania.

Jeannette and Daniel were the parents of five children born in Norwalk. The Ferguson Family Bible lists births of him, his wife, and children.

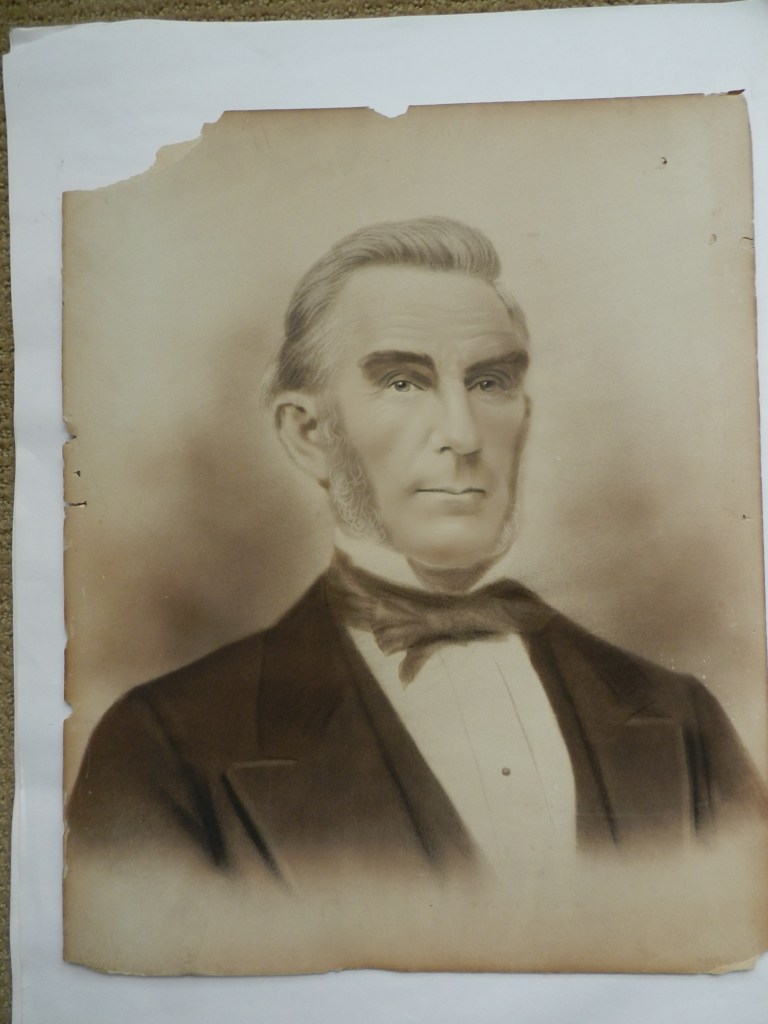

Daniel H. Ferguson was born March 18, 1816.

Jennette Keeler was born July (illegible),1816.

Elbreannah Ferguson was born May 2, 1839.

Frances Anne Ferguson was born April 17, 1841.

Elbert Frances Ferguson was born May 21, 1843.

James F. Ferguson Aug. 16, 1845.

Margaret St. John Ferguson Oct. 24, 1847

In the summer of 1842, Jeannette Ferguson had black-edged cards printed. The cards said Mrs. D.H. Ferguson. She had much to mourn. On June 16, 1842, her first child, a daughter, Elbreannah died. Less than a month later, July 8, 1842, Frances Anne died. Jeannette and Daniel buried their girls in Danbury at the Wooster Street Cemetery in the graveyard behind the jail.

Shortly after their last child, Margaret St. John, was born the Fergusons moved from Norwalk to Danbury. The people of Danbury still made hats.

Danbury was the “town to be in” if you were in the hatting business in 1840. In 1820 there were twenty-eight hat factories in Danbury. The raw materials needed to make beaver skin top hats grew in the woods and rivers nearby. The beavers lived in the streams. Woodmen cut trees for wood. Workers used water power from the rivers to drive the machinery. Making beaver fur into hats requires heat, moisture and pressure to felt the fur. Then hatters shaped the felt into hats. By 1831 the number of people involved in the hatting business surpassed the number in all the other Danbury businesses put together. By mid-1840s the hatting business became mechanized. Hatter manufactured more hats in Danbury than anywhere in the United States. Danbury was known as Hat City.

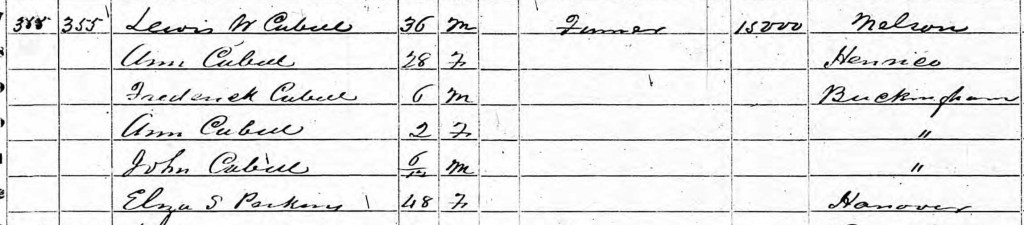

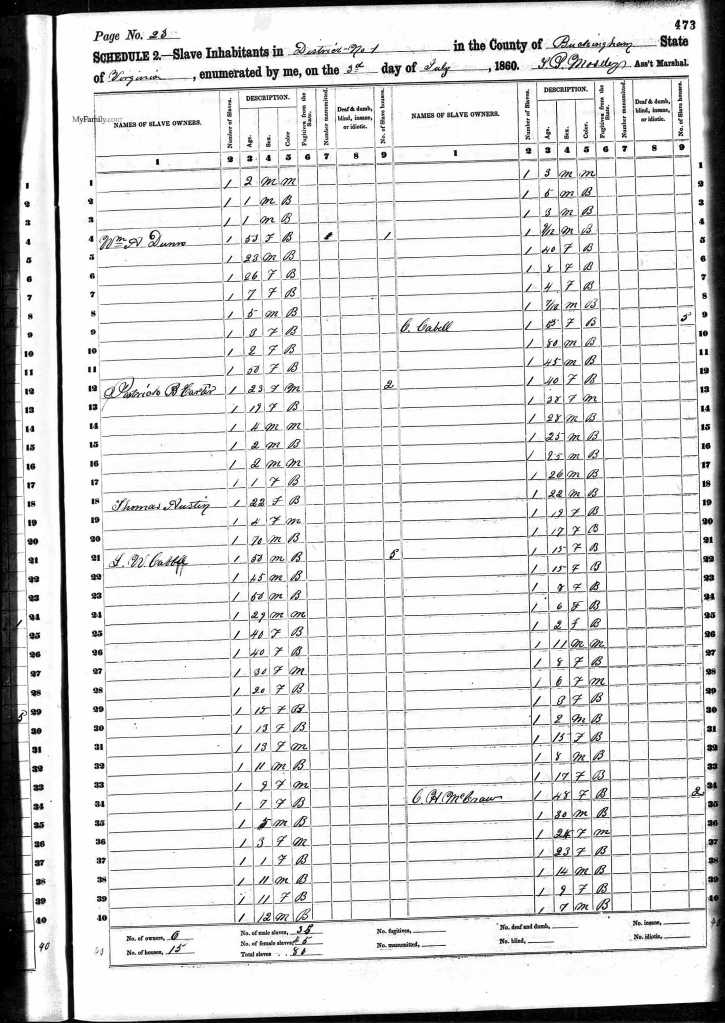

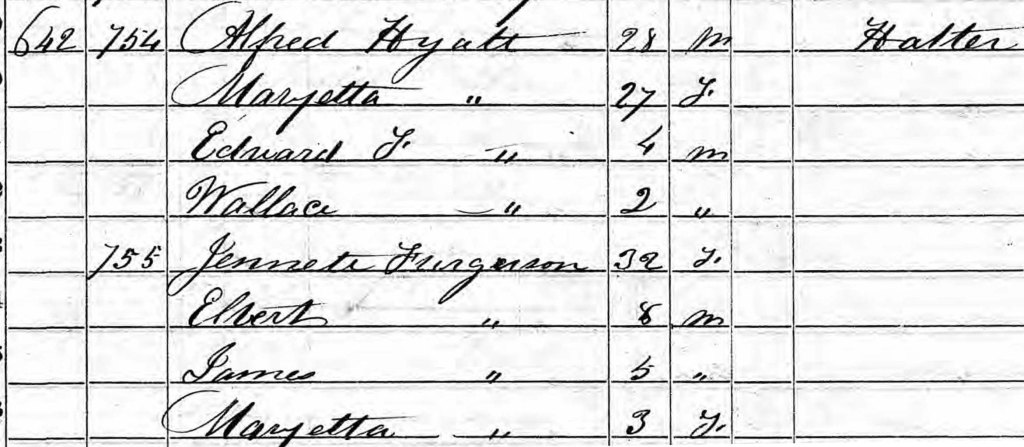

While Daniel sought gold in California, Daniel’s family lived with Jeannette’s younger sister, Marietta Keeler Hyatt, her husband, Alfred Hyatt. Alfred, head of his household, was a hatter. Marietta and Alfred had two boys, Edward and Wallace. The 1850 federal census lists these eight people living in one housing unit, dwelling number 642. Alfred Hyatt is listed as head of family 754 and Jeannette (Jeannette), age 32 is head of family 755. Her three children are- Elbert, age 8, James, age 5 and Maryetta (Margaret), age 3. James and Elbert attend school.

Here is a photo copy of this 1850 record from Danbury

Daniel Ferguson Make an Entrance

Jeannette worried that Daniel had not arrived home by Christmas as planned, but he did get there before 1850 ended.

He arrived in Norwalk harbor aboard the SS Ohio with Captain Schenck at the helm. Daniel had hoped to reach home before Christmas; the Ohio had just departed from Havana on December 18th on time. Shortly out of the Havana harbor one of her engines blew out so she returned to Havana for repairs. She resumed her trip on the 19th making good headway until the 22nd of December when a gale hit. Having only partial power she sat out this storm; then shortly after getting underway she sprung a leak. Passengers and crew alike bailed water out a little faster than it came in. The Ohio reached the wharf at Norwalk on December 26, 1850.

To Oregon

Did Jeannette want to travel thousands of miles to the west coast? It would be a hard trip with three children. Her youngest, Margaret, was only four. But Daniel did convince his wife to go west with him.

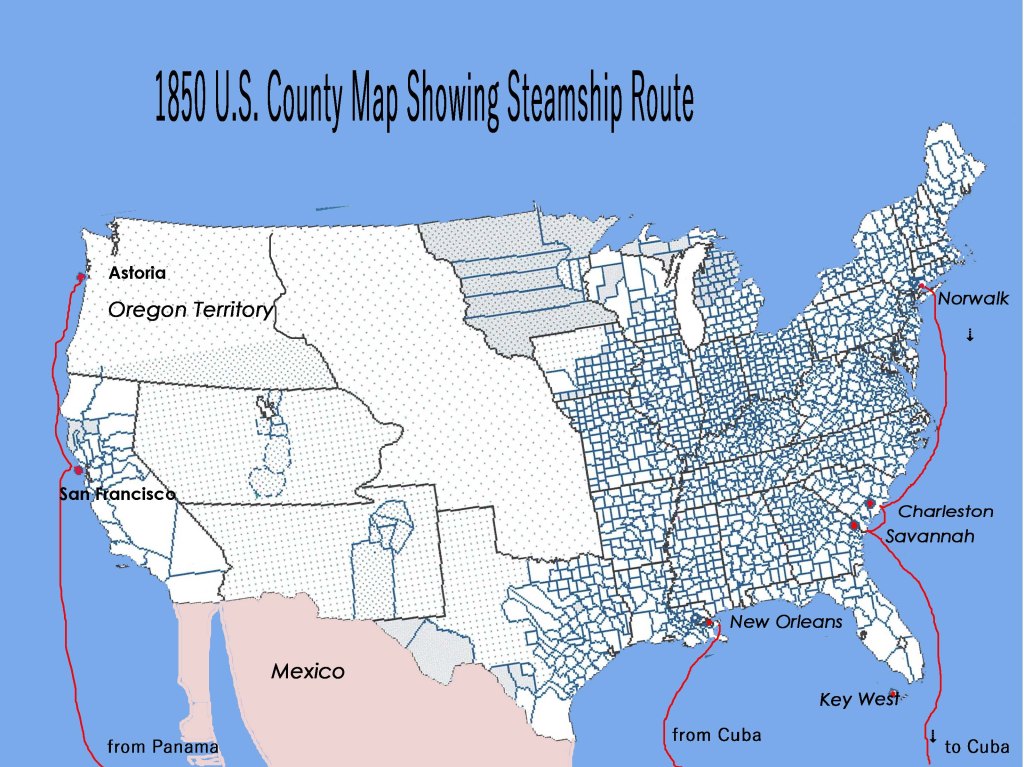

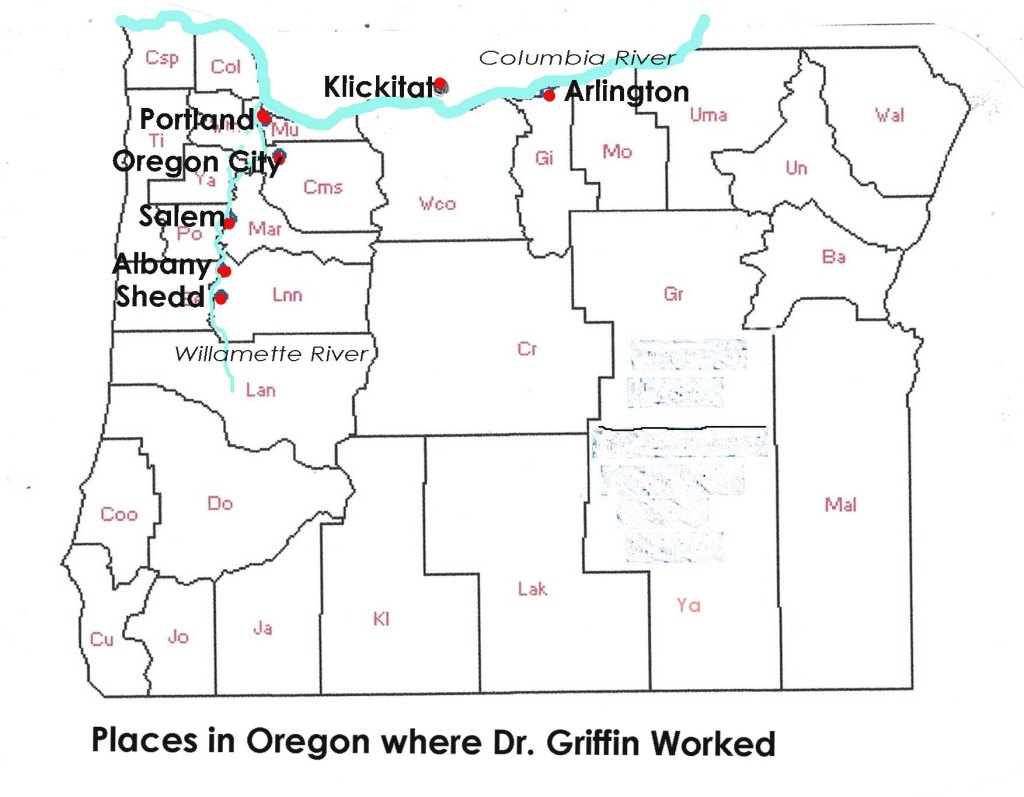

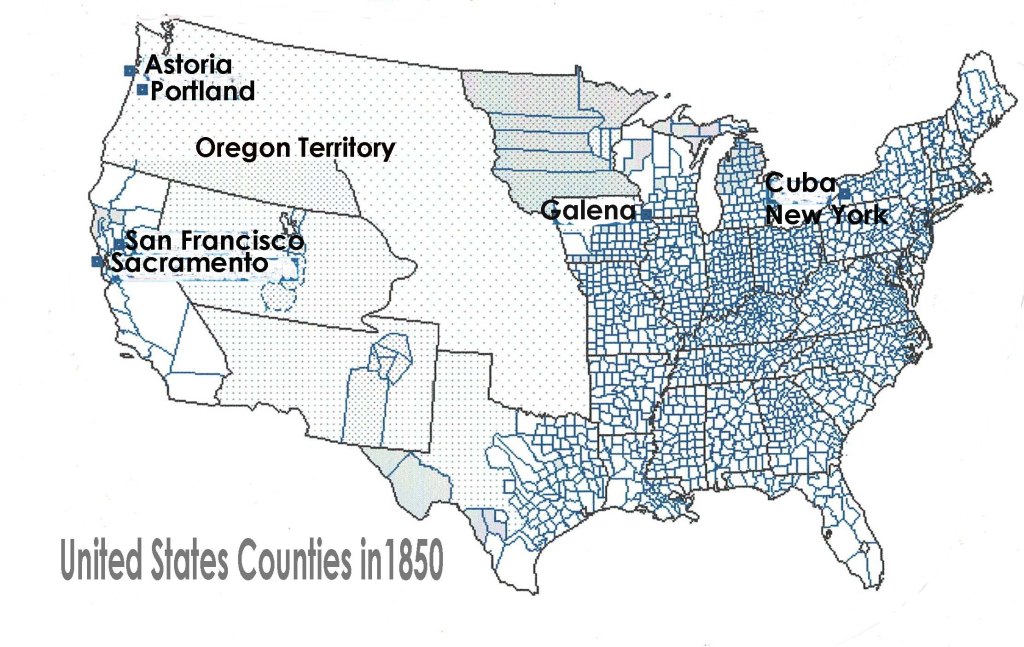

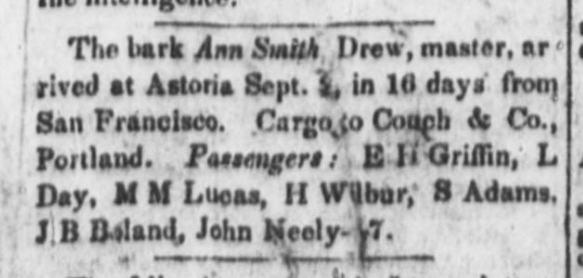

The next time Daniel traveled his family came with him. His family included Daniel himself, Jeannette, Elbert, James and Margaret. They traveled the same route as Daniel had. This time Daniel was a rich man and who bought the nicer lodgings in comfortable ship quarters. There were goodbyes to be said, items to buy and letters to write. The boys finished a term at school. Also, they needed to consider the best season to cross the Isthmus of Panama. Cholera, although always a risk, was at epidemic proportions in the rainy season. On the first leg of their journey, they traveled by boat from New York to Chagres. The second leg across the Isthmus started at Chagres where they boarded flat-bottomed boats. Men pushed the boats up the Chagres River with poles to Gorgona. After Gorgona they rode mules to Panama City. Alligators, monkeys, parrots, and mosquitoes buzzed, hummed, screamed, and showed their teeth. Yellow fever, cholera, and malaria still sickened travelers. They were brave to come, and they survived the crossing of the Isthmus. The trip from Panama City to San Francisco was tame compared to crossing the Isthmus. But it was long and usually took two months by boat. When they reached San Francisco, they visited places and people Daniel knew. They arrived in Portland, Oregon sometime in 1852. They finished the ocean voyage part of their trip at Astoria as their destination was Portland, Oregon, USA. The Columbia River enters the sea at Astoria; canoes and small river steamboats took travelers on to Portland. In that year according to Claude-Alain Saby, Portland’s population was about 4000 people.

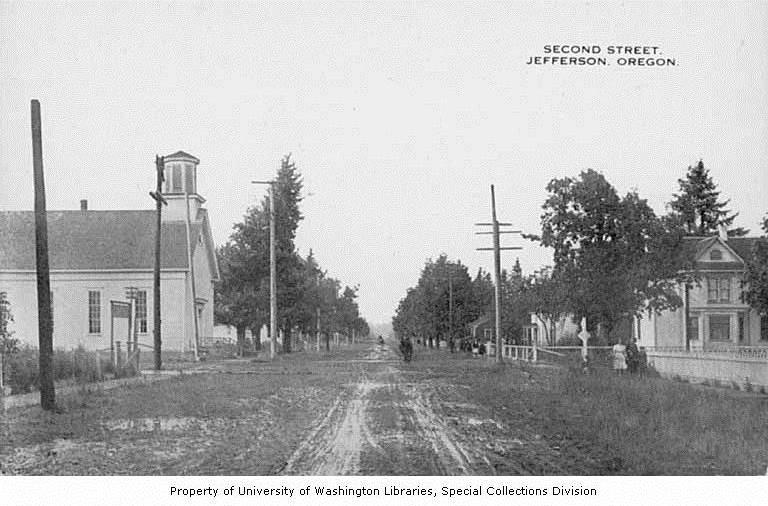

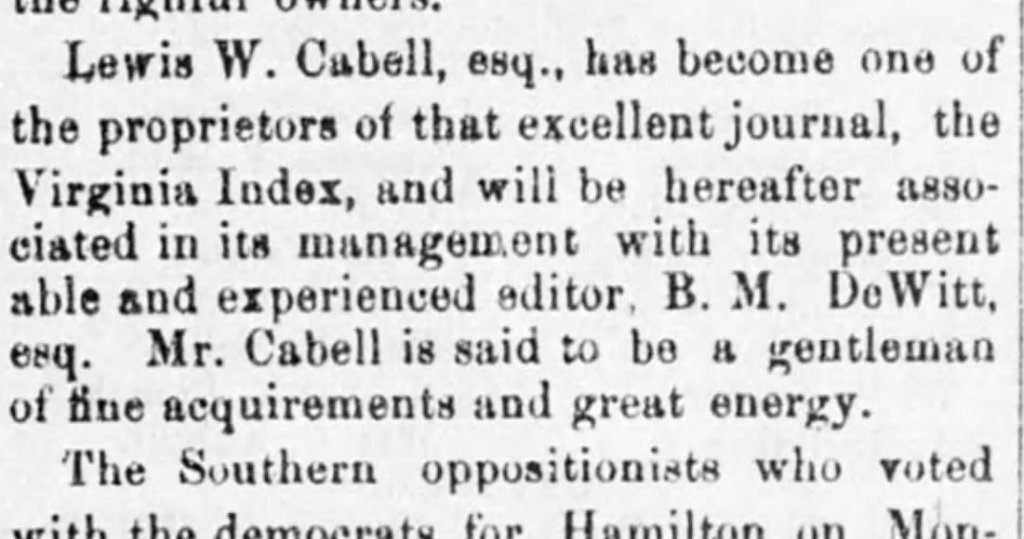

Elbert Ferguson, who about 10 when the family arrived, died on December 9, 1863. Quite a while before this event, the Fergusons had established friends and a residence in Portland on 2nd Street. Here is a copy of the newspaper notice.

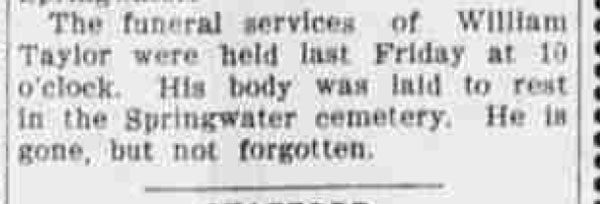

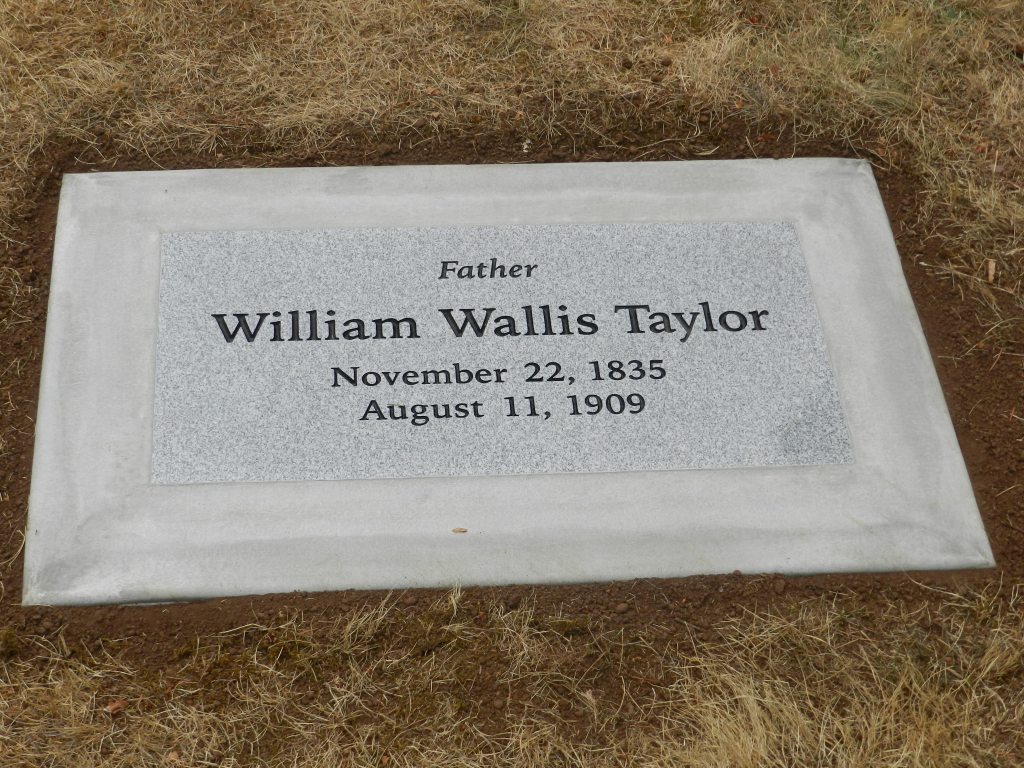

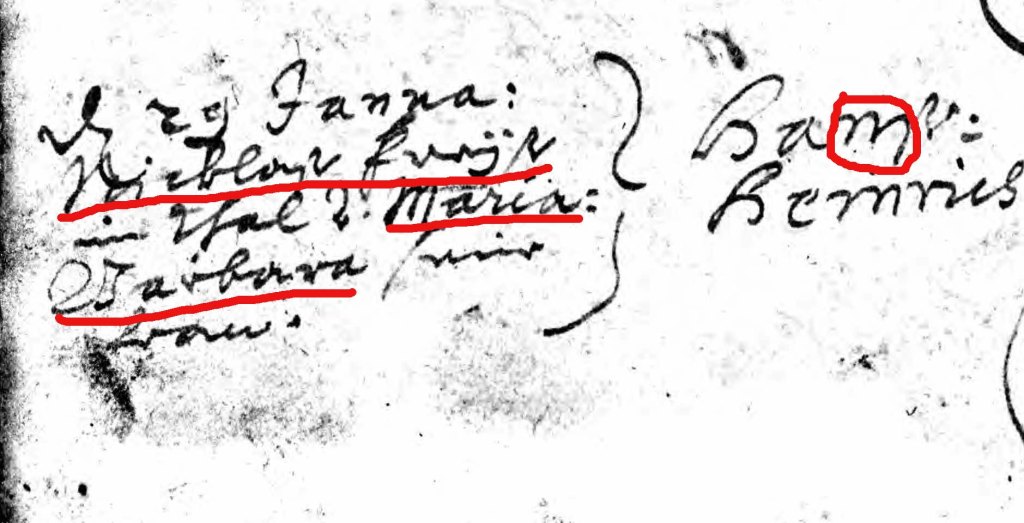

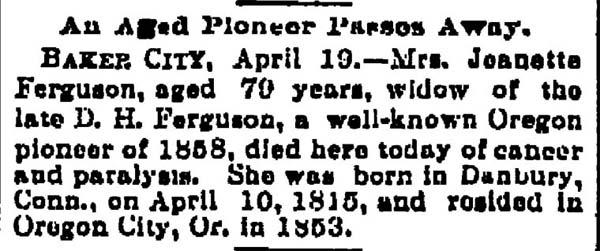

Daniel, being restless and enterprising, would convince Jeannette to go with him many more times. In the end she outlived him. Here is her obituary.

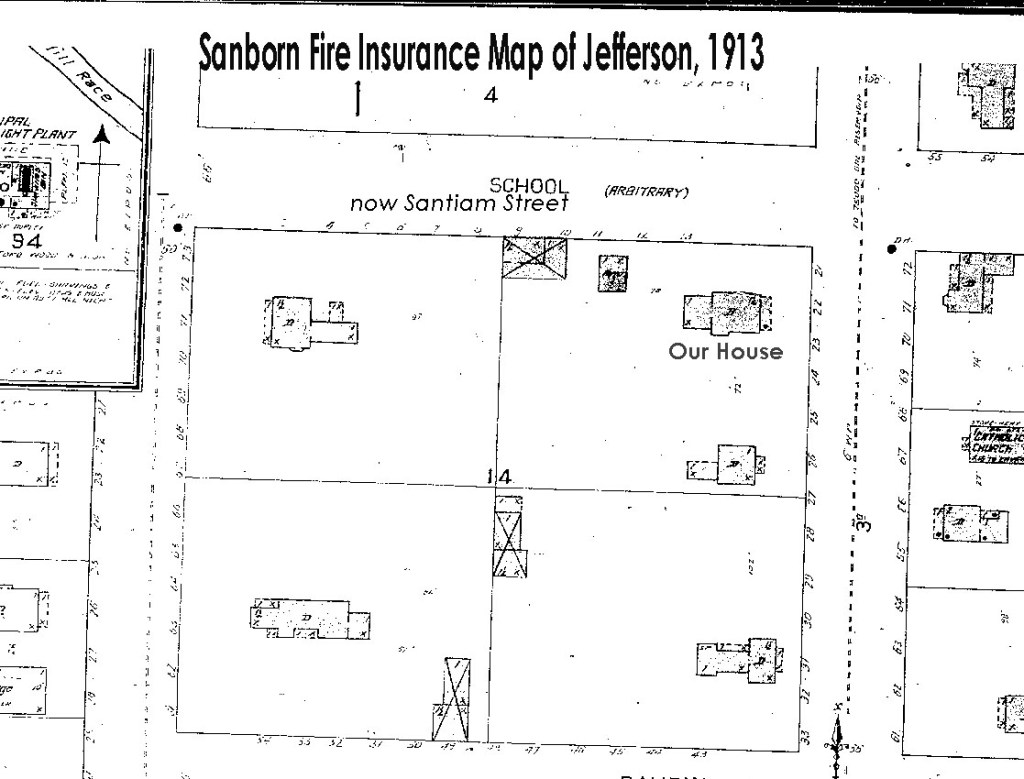

This obituary, published in The Morning Oregonian on April 20, 1984, has some mistakes. Bible records put Jeannette birth in July of 1816. The family came to Portland, Oregon and built a house before moving to Oregon City. Daniel lived in Oregon City alone in 1853. He is recorded in both the 1853 Oregon Territorial census and the 1857 census. The 1853 census recorded him as living alone in Oregon City. In the 1857 record, he is shown with his family. So Jeannette was living in Oregon City by 1858. It looks like whoever wrote the obituary switched the 1853 and 1858 dates.

Why Jeannette moved to Oregon City

Soon after the Fergusons set up housekeeping in Portland, Daniel started traveling to Oregon City. Oregon City is located 12 miles up the river from Portland. Two steamboats took passengers between Oregon City and Portland. One, the Portland, was a side wheeler. The other, the Multnomah, was a stern wheeler. The Multnomah ran every day except Sunday. The Portland ran a couple times a week. On July 2, 1857 the Multnomah fell over the falls at Oregon City putting her out of the picture.

Jeannette wanted to see her husband more than twice a week. She and the children moved to Oregon City as shown in the 1857 Oregon Territorial census.

Another Piece of this Story to Come

The next piece is about Daniel’s project in Oregon City and a fatal fire. Another piece of Daniel Ferguson life is included in Traveling by Mail Boat.