Hunting for Mary Lucina Taylor

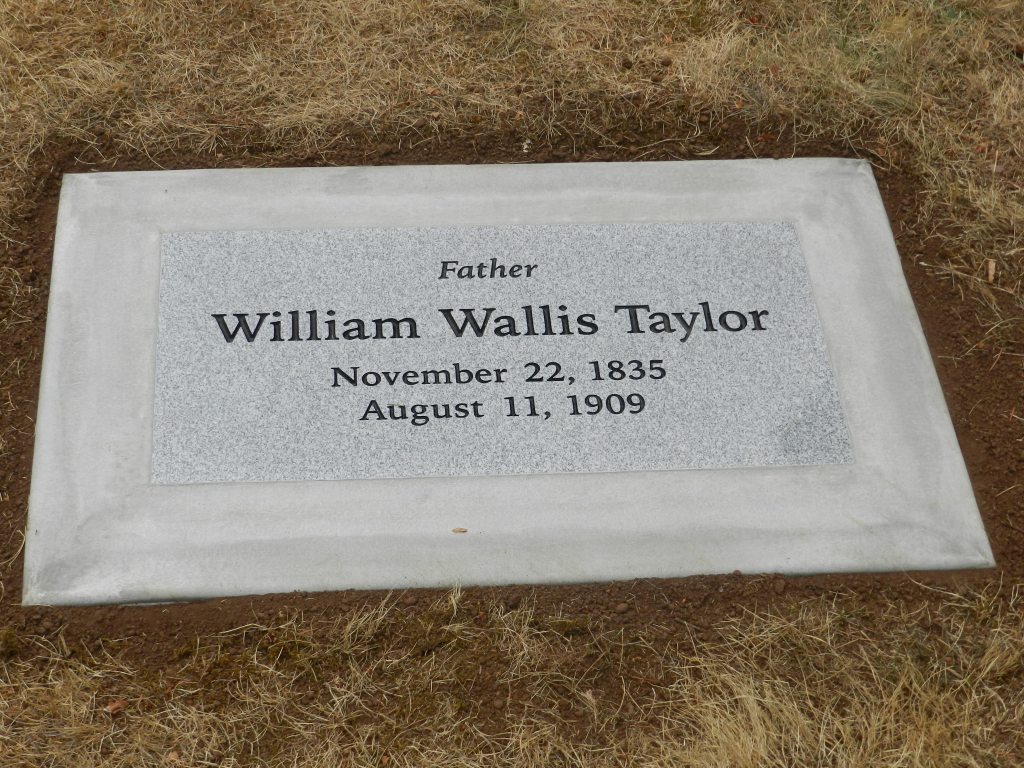

Why do these stories sometime take on a life of their own? This story was to be about an institution and an institution is involved. Death of a loved one is a somber time for families, marked with family gatherings, funerals, burials and graves markers. This story involves two stone grave markers both made long after the deceased had died. One marker made for William Wallis Taylor was set in 2015. The marker for Mary Lucinda Taylor Miller was completed in 2006.

I wrote this story about my husband’s 2nd great grandparents and their daughter, Mary Lucina. I searched for years for Mary’s death date and burial place. The institution involved in Mary’s last years was Western State Hospital at Steilacoom. This hospital is located between Olympia and Tacoma, Washington. I had been looking for Mary about 15 years before I found a death date.

William Wallis Taylor’s Marker

Craig, my husband and I became acquainted with one of his cousins. This cousin also traced back to Craig’s 2nd great grandparents, Mary Ann Sayles and William Wallis Taylor. We met and traded records. I had found Mary Ann’s grave site in Springwater Cemetery in Clackamas County, Oregon. The cousin’s family held the bible of William. The dates and places in both our records matched.

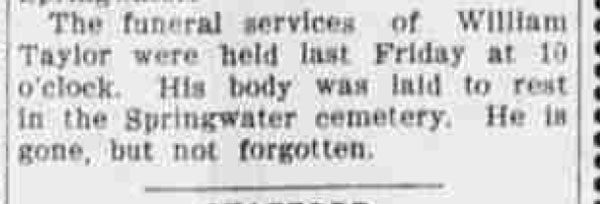

Both the cousin and I had found an obituary of William’s saying he had died at the home of his son near Aurora, Oregon on August 11, 1909. William was buried in Springwater Cemetery where his wife Mary was buried. Here are copies of William’s obituary and funeral notice from the Oregon City Enterprise, dated 20 August 1909.

We were sorely disappointed when we visited Springwater Cemetery and didn’t find William’s burial next to Mary Ann’s grave marker. We searched the entire small cemetery. Craig’s cousin convinced the combination groundskeeper and cemetery record keeper that William Taylor was buried there next to his wife. We had a new marker made. It was placed to the left of Mary Ann’s grave site.

Here is a photo of this new marker.

Mary Lucina Taylor Miller

Before this event, I knew quite something about William and Mary Ann’s first child, Mary Lucina Taylor Miller. Mary was my husband’s great grandmother. I had become acquainted with the cousin’s grandmother, Madeline Taylor Wells. She was the granddaughter of William and Mary Ann Taylor and had family photos of her Aunt Mary Lucina.

Mary Lucina and Siblings about 1865

Mary Lucina seated in the middle

Born in LaPorte County on 7 Aug 1857

Orril Adell on the left

Born in Will County, Minn. on 18 Sep 1862

Otha Beardslee on right

Born Will County, Minn. on 6 Sep 1864

Mary Lucina Taylor and Edward Arthur Miller

Wed in Multnomah County, Oregon on 28 Oct 1885

Taylor Family about 1896 in Springwater, Oregon

Edward Miller on left

Mary Lucina Miller in back

Daughter, Edna Naomi Miller

Born in Dodge, Clackamas, Oregon on 24 Aug 1889

They homesteaded a farm in the Dodge Springwater area

Move to Portland, Oregon

By 1910 the Miller family had sold their farm in Dodge, Oregon. They now lived in Ward 8 of Portland, Oregon. According to census records, Mary and Edward had been married 25 years. Edna Miller, their twenty-year-old daughter, lived with them and their house was on East 35th Street.

In 1912, Edward A Miller and his daughter Edna N Miller still lived at at 192 E 35th Street. This information comes from to the 1912 City Directory of Portland, Oregon, Mary is not listed on this record.

I found Mary in the 1915 City Directory of Portland, Oregon. She is listed as Mary L Miller, widow of Edward and living at 4927 66th SE. Twenty-four years later she still identified herself as a widow of a man named Miller. On her death certificate it is noted that the first name of her deceased husband is not known.

Edward Living St Joseph, Michigan

Edward filed for divorce on 1 December 1917 at the courthouse in St. Joseph, Michigan. The grounds were desertion. Edward was the complainant. His divorce was granted on 22 July 1918. He married Bessie Gadson on 18 August 1918.

Daughter Edna Married

Before Mary entered Western State Hospital in 1929, her daughter, Edna had lost her first husband and married a second, Charles Foster. She brought to this second marriage a small boy, Howard Shelton, son of her first husband. She and Charlie had 3 children. Charlie informally adopted Howard. Howard was a teenager when his grandmother, Mary, lived at Western State Hospital. He visited Mary there and remembered these visits being sad.

The Institution on the Cowlitz River

Many years before in 1854, the “Poor Law” was passed by Washington Territory. Its aim was to find a better way to care for and house for the poor, disabled and mentally ill. It shifted the support of these individuals from their families to the counties where they lived. At first patients were cared for through a contract system.

Twenty-one such person went first to a place in Monticello (now Longview, Washington). It was located along the Cowlitz River in Cowlitz County.

This institution was set up by a pair of businessmen from Monticello. They knew how to make money, but not how to care for “this class of sufferers”. James Huntington and his son-in-law, W.W. Hays built and ran this place. They received a dollar a day for each patient under their care.

A big problem for this enterprise was the location. Here is a quote from Starlyn Stout’s Care For the “Unfriended Insane in Washington Territory (1854 to 1889)”.

The buildings of the asylum were revealed by the elements to be merely temporary. In his history of the region, Hubert Howe Bancroft surmised that accommodation opposite Monticello on the Cowlitz River were inadequate. So much so that an event of melting snow from Mt. Rainier brought on an “unusual flood” in December 1867, in which the improvements were swept away. Huntington’s hastily built buildings were now needing to be hastily salvaged and rebuilt to maintain his part of the contract. They published a letter addressing community concerns about their facility, claiming that they too were victims of the territory not fulfilling its part of the agreement. “The Territory must meet the expenses as per contract… We only ask that our money be paid when due”.

Dorothy Dix

A 19th century social reformer, Elizabeth Meriwether Gilmer, who was better known by her pen name, Dorothy Dix, had friends inspect this place in 1869. She wrote:

Just as I was prepared to leave for California, I first learned from some military officers and reliable civilians your territory was responsible for a rightly intended provision for certain unfriended insane men and women … It being impossible to visit the place referred to myself, I earnestly requested an experienced medical man and a carefully judging citizen of Oregon to see if the statements … were borne by facts, as they understood right care for this helpless, irresponsible class of sufferers. (“Miss Dix on the Insane”).

It was found that some patients were doing all the cleaning, laundry and cooking. Other patients were confined to their cells. Filthiness was found throughout the faculty.

Dorothy wrote about this. When Dorothy mentions the Doctor and Inspectors, she is talking about Washington county people who were responsible for the asylum.

The patients sleep in bunks, in cells, in a coarsely finished, unplastered building, parts of which are described to me as very little better than a barn … the visitors added that, judging from any efficient and proper standard, they could not consider the institution otherwise than inadequately provided both for care and cure of the insane … badly maintained by parties in charge, who possibly may know no better … The Doctor and inspectors are parties interested in perpetuating the present system; the ‘one by his salary easily earned, the others by trade’” (“Insane Asylum”).

More Letters from Dorothy Dix

She also wrote to two authorities in Washington Territory—Governor Alan Flanders and former Governor Elwood Evans. Changes were made. After relating her assessment of the situation, she said this. “At this distance I can only write to you, sir, knowing your sense of pity for these poor creatures will induce early and, I hope personal attention.

Changes Were Made

Fort Steilacoom, an old army base which had been built in 1849, was out of use and run down. On April 22, 1868, the staff lowered the last flag at this army fort. The fort located in the Puget Sound region near Tacoma, Washington would be the new home for 21 Monticello patients. The new inmates who had lived with the conditions at Monticello bought their stories with them. Even to this day their tales of poor treatment and the demons that haunted them abound.

In 1887, the Washington Territory legislature approved $100,000 to build a new institution on the Fort’s grounds. In 1888 this institution became known as Western State Hospital for the Insane. In 1915 the institution’s name was changed again- this time to Western State Hospital.

My Search for Mary’s Death and Grave

Before Craig and I knew that his great grandmother, Mary Lucina Taylor Miller, had spent her last years in a mental institution, we were puzzled by the lack of results in the hunt for her death date. Because she was a direct ancestor to my husband this lack was an ongoing source of frustration. I had looked in both Washington and Oregon death indexes many times before I found her in the Washington death index. I ordered her death record from the Washington State Department of Health. I did the paperwork showing my husband, who was requesting the record, was her oldest living direct relative. Since Mary had died in 1939 this record was about 75 years old when I finally got it.

Mary had lived at Western State Hospital for almost ten years when she died on March 9,1939. She died of a heart and lung condition. Senile psychosis was said to be a contributory cause. She was cremated on March 14, 1939.

Also, from the death certificate, we learned Mary had entered Western State Hospital on August 27, 1929. She died on March 9, 1939, and was cremated there on March 14, 1939. Her hometown was Washougal, Washington.

Disturbing Article in Spokane Newspaper

The Title, Bill Could Help Families Find Ancestors’ Graves, hints that there was something in the Washington State laws preventing family from locating relatives who died in Washington State’s mental institutions. A Washington State statute designed to protect the mentally ill from shame restricted anyone from getting their relative’s death certificates. This statute prevented a volunteer organization called Grave Concerns from identifying who was buried and where they were buried in the institution’s cemetery. The state had decided these patients were people to be ashamed of and hid their records. Here is a quote from the article.

At Western State Hospital, a facility worker once found a shed full of human remains packed into tobacco tins and canning jars. And at Northern State Hospital in Sedro Woolley. Wash., now closed part of the cemetery was plowed under and farmed.

Cremated remains were often buried together in mass graves, said Laural Lemke, Western’s ombudsman and chair of The Grave Concerns Association, a volunteer group that repairs grave sites. After the 1950s, many unnamed remains were sent to crematoriums.

Making the job of restoring dignity to Western State Hospital’s cemetery was the fact that “many of the state’s records of the dead are incomplete or missing even when records are located…the cemeteries which volunteers have only recently began to recover are often overgrown and in disrepair.

Our Visit to Western State Hospital

Craig and I met Laurel Lemke, a woman greatly involved with the Grave Concerns Association, on March 10, 2015. She described life at the hospital when Mary lived there.

Mary slept in a narrow bed in a narrow room with few personal belongings and a barred door.

Because Western State Hospital grew its own food and kept livestock, Mary had plenty to eat. At this time the Great Depression was causing misery throughout the land. Patients worked on the farm. Mary may have worked preparing food or sewing. Physical labor was considered therapeutic.

From 1911 to 1961 hydrotherapy was used to sedate patients. Bath treatments of 2 hours included hot and cold water sprayed up and down a patient’s spine.

Washington State Hospital’s Cemetery

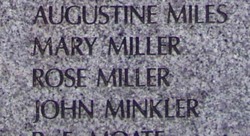

Before we left, Laurel showed us the cemetery. Volunteers for Grave Concerns had been restoring and upgrading the grave sites for about ten years. It was no longer tangled in blackberries with graves only marked with numbers etched on small concrete squares. The Grave Concern Association had found names to go with the numbers. As they raised money, they replaced the old unreadable number blocks with granite grave markers. These markers showed the patients name, the birth date and death date. Here is an example.

We were hoping to find Mary’ grave marked like the marker on the right. We had set a granite grave stone for her father, William Willis Taylor buried in Springwater Cemetery.

This was not to be. It is sad to say Mary’s remains were among the unidentified. Perhaps, her unidentified remains were in a canning jar or tobacco tin found stored in the garden shed. Her remains were buried in the mass grave with a large granite marker. Her name and dates were there. We laughed and cried that day. Here are some photos.

Leave a comment